Last September, at the “Paths to Freedom” (Sentieri di Libertà) event in Servigliano, I had the pleasure of meeting Linda Quigley, daughter of British POW David Garcia, Linda’s daughters Annabel Heath and Miranda Quigley, and Miranda’s husband Roger Bickmore.

Pte. David Garcia, 1/4 Battalion, Essex Regiment, was deployed to North Africa during WWII, and was captured near Mersa Matruh in June 1942.

Unlike most POWs featured on this site, David had not been an internee in PG 59 Servigliano. Rather, he was interned in PG 102 L’Aquila, nestled in the foothills of the Apennine Mountains some 130 kilometers (around 80 miles) south of Servigliano.

Following the September 1943 Italian Armistice, prisoners of PG 102 left the camp. A War Office document, dated April 1945, in the British National Archives, explains:

“After the Armistice with ITALY had been signed, the Italian Commandant opened the gates of the camp and marched the P/W out into the hills, as it was reported that Germans were approaching. A certain number of escapers were rounded up by German paratroops and taken back to camp, but the majority got safely away.”

David and another escaped prisoner, whom the family believes was named Patrick, made their way to San Giacomo, where they were protected by the family of Umberto Capannolo.

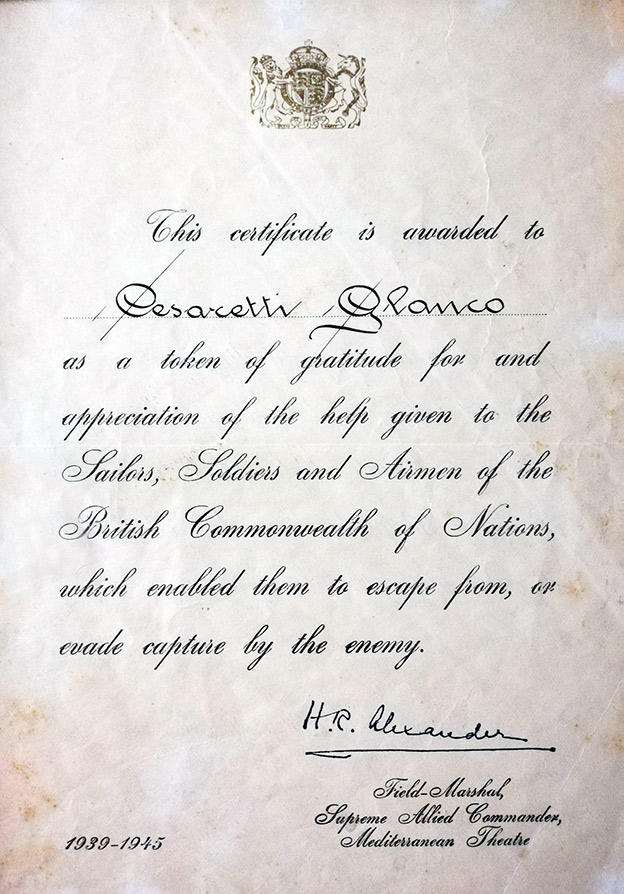

The exact dates that David and Patrick were with the Capannolos is not known to the family. However, David retained a slip of paper certifying that he had “rendered a statement of his experiences to the British Section, C.S.D.I.C., C.M.F. [Combined Services Detailed Interrogation Centre, Central Mediterranean Forces].” The document is dated 5 July 1944, therefore David may have been on the run in enemy-occupied Italy for as long as 10 months.

On returning home to England, David attempted to contact the Capannolo family in order to let them know he was safely home and to thank them for their kindness.

When the letter was returned to David, he wrote to the British Red Cross asking if they would assist in his contacting the family.

Continue reading