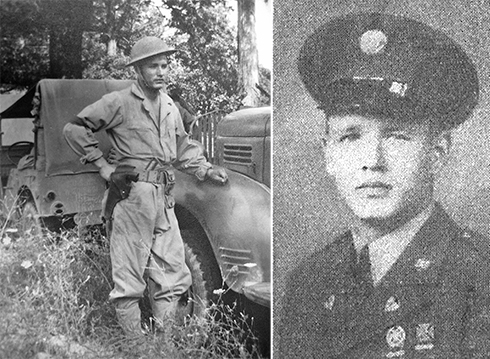

Louis VanSlooten before going overseas

I have known Louis VanSlooten’s son Tom VanSlooten since 2008.

Tom was one of the first family members of Camp 59 POWs I met when I began my research into the camp’s history. I met him through email the same month I began this site.

Tom’s dad was living and active then.

At the time, Tom wrote, “My father has been writing his story off and on for many years and has recently started writing again. It has been a difficult task for him. He told me just a week ago when we were at our family cabin in Northern Michigan that he has spent 65 years trying to forget what happened, and now is having in some way to go back and relive it again to write it all down.”

Louis came close to finishing this memoir before he died in 2011. His granddaughter (Tom’s niece) Jessica Lyn VanSlooten edited and completed the story, which I am pleased to share in this post.

The story is full of excellent detail. Of particular interest to me are the attentiveness and lifesaving efforts of the camp medical doctors, Captain J. H. Derek Millar and Adrian Duff. In his research, Giuseppe Millozzi references Dr. Duff as having cut his own arm, collected blood, and then donated it to his patient through a rubber tube. As it turns out, Louis was a witness.

Camp 59 Survivors contains a number of posts on Louis’ friend and fellow escapee Luther Shields. Access those posts by picking “Luther Shields” through the “Select Category” search button.

The site also has information on the Palmoni family, who helped Louis and Luther. Read “Marino Palmoni on the Sheltering of the POWs” and “A Visit to the Palmoni Home.”

Tom mentioned other families who helped Louis and Luther as well. “Here are the names and addresses of some of the Italian people that helped them survive after the escape from Serviliano prison camp.

“The Maurizi family was very special to my father. My father always referred to the mother of Umberto as Grandma. Grandma would sometimes argue with Umberto because he was afraid for the family’s safety with my father and Luther hiding there. Grandma would say, ‘Louis is like my son, he will stay.’ This touched my father and he will never forget it. When the time came for my father to leave they knew Grandma would be very upset, so they decided they would have to leave on a Sunday morning when Grandma was at church. It was difficult for my father, but the time finally came when they knew they had to go. Later, when my father returned to the U.S., he sent a package of various items he knew they could use, and in that package was a special winter coat for grandma with a note from him to her inside the pocket.”

Corradini Giovanni

Smerillo, Prov. Ascoli Piceno

Marche, N.7, Italy

Maurizi Umberto

Gualdo, Prov. Macerata

Castello, No. 21, Italy

Mercadili Gina

Contrada Castello

Gualdo, Prov.

Macerata Marche, Italy

The Story of Louis J. VanSlooten’s Service, Capture, and Escape during World War II

Written by Louis J. VanSlooten, edited by Jessica Lyn VanSlooten

Copyright Jessica Lyn VanSlooten, August 2016

Foreword

Sergeant Louis “Louie” J. VanSlooten was an engineer in the First Armored Division, “Old Ironsides,” in the U.S. Army during World War II. He, along with 18,500 other U.S. soldiers, participated in the Center Task Force during Operation Torch, a comprehensive military plan for the Allies to take over the French North African front.

This memoir, written by VanSlooten during the early 2000s, chronicles some of his experiences during Operation Torch, his capture and imprisonment, and his escape. There is much more to his story, including his eventual rescue; he was unable to record these additional details before his death in 2011. Van Slooten asked me, his granddaughter, to turn his notes into a narrative. I have, to the best of my ability, followed his meticulous notes and directions, written in the margins of his handwritten manuscript, to create a chronological narrative of his experiences. At times, I’ve added some historical context or detail, but I wanted to preserve his words, phrasing, and tone. The story and format of this narrative is all his. It was a great honor to be entrusted with his story; by editing his words and researching these events, I came to understand my grandfather better. His desire to avoid attention from authorities, his fear of certain loud noises, and his love of ice cream—daily decadence after so many months of near starvation—make much more sense knowing the struggles and deprivation he faced for 18 long months.

With a world of information available through the Internet, I was able to research the places VanSlooten details throughout his memoir and, in some cases, learn the fascinating history behind these landmarks of his time as a POW and escapee. For instance, the convent in Montefalcone Appennino must certainly be the Chiesa di S. Giovanni Battista, the Church of Saint John the Baptist. Historical documents suggest that the ancient convent located near this church sheltered monks from the Abbey of Farfa, who fled Sabina to escape Saracen attacks in the ninth century. This holy site continued to provide shelter to those in need many centuries later.

Training

We trained in Northern Ireland from May to August of 1942. We learned how to build a bridge from ship to shore, but we didn’t know where we would use this skill. The uncertainty continued even as we moved our training to Alderley Edge, in Chesire, England in September. In October we moved to Wemyss Bay, on the coast of Inverclyde in Scotland, where we spent a week loading our equipment on the same ship we had been training on. Our time in the British Isles was coming to a close. We sailed for three weeks before those in command told us we were going to be invading Algiers, Algeria in North Africa. On that night, our ship sailed through the Straits of Gibralter into the Mediterranean Sea. After two more days of sailing, we headed toward shore under the cover of night. We were approximately 20 miles east of Oran, Algiers—our invasion point.

The Invasion

Our objective was to move inland and capture the town of Lourmel, Algeria and the airport bridge there. Once there we would travel further and capture the road bridge and train bridge, as well as mine them for demolition. We faced a few obstacles, including a French liner that tried ramming the ship at 4:00 in the morning on November 8. For our work inland, we had tanks, half-tracks, and Jeeps, all of which were waterproofed for our invasion. We were told that 10,000 French Legionnaires might counter attack us.

On Armistice day, November 11, 1942, we were ordered to the Oran Airport assembling area to await further orders. We were told to load our equipment on flat cars and proceed to the Tunisian Front to push the enemy back. We loaded the equipment and then waited two days to move. Our orders changed, and we unloaded once again. We drove 500 miles, across the Atlas Mountains, to reach Tunisia.

The Front Line

As we drove across the Atlas Mountains, we were attacked by Arabs on horses as we stopped for refueling. After a brief 15 minute firefight, not many were left, though a few of our attackers escaped.

On Thanksgiving night, November 26, we were a few miles from the Front. We pulled into an olive grove for a hot meal at 10:00 pm, and by midnight we were back on the road. We were headed to relieve the English troops. We arrived at the Front as dawn broke, and took position. We were ready to attack.

Our tanks charged in and the battle was on. Our light tanks, with 37 mm guns, were outnumbered. The enemy had Panzer IV tanks with 75 mm guns that could move 360 degrees; our guns could only move 60 degrees. We battled all day. At night, we holed up in another olive grove and waited for dawn to begin again.

On the second day, approximately 50 tanks battled. At any time at least a dozen tanks were burning—some burned all night. Many wounded and dead soldiers lay everywhere; when a tank was hit and burned, the people inside escaped through the turret if they could. Jumping through the fire caused the tips of noses and ears to be burned off. When morning arrived, we were not attacked.

Several days after this tank battle, we were surveying the area using our binoculars and spotted several of our tanks and half-tracks that appeared to be salvageable. We headed out around 10:00 that night to inspect the “No Man’s Land.” Our trip was scary because there was a chance the Germans were doing the same thing. We discovered, unfortunately, that our tanks were not worth recovering. And, all of the tanks contained dead crew members. The half-track was in decent condition so we drove it back to our olive grove.

The next morning, I went to inspect the half-track. I stood on the running board to survey the vehicle and everything seemed to be in working order. Suddenly, the back of my neck began to bristle with warning. As I turned my head to step down to the ground, a bullet flew by my left ear and made the snapping sound that tells you it’s very close. What or who caused that warning at the back of my neck?

I believe. I know.

Later that morning we captured two German snipers hiding about 200 yards out in No Man’s Land. They carried sniper rifles equipped with special telescopes that were capable of spotting a target a mile away. The two men were taken to the rear. For them, the war was over.

We held our position for ten days and entertained ourselves by lobbing shells at the enemy, and they obliged by returning fire. Twice a day the enemy sent Stuka dive bombers over, three bombers carrying four bombs each, for a total of 24 bombs a day, 240 bombs after the end of the ten days. When the Stuka bombers hit, we would use a well for a fox hole. This dry water well was approximately eight feet in diameter and eight feet deep. It could hold six of us. We tied a rope to the remains of an olive tree to lower ourselves down and hoist ourselves up. It would take a direct hit to get us, and one time it almost did.

That day, four fellow GIs crouched against one wall of the well, and my buddy Lofty and I huddled on the other side. As the Stukas started diving at us, their sirens blaring, one of the GIs decided to change his position and squeezed in between my friend Luther “Lofty” Shields and me. The bombs were now exploding around us with earth-shaking force. A piece of shrapnel landed in our well and struck the fellow who had squeezed between Lofty and me. The shrapnel stuck the edge of his helmet, tearing a hole through it and taking his eye out. What was left of his eye was still attached to the eye socket and stuck to his cheek. The shrapnel continued downward and took off the heel of my shoe. It was a close call. I wondered if Lofty or I would have taken the hit if our fellow soldier hadn’t decided it would be safer on our side of the well…. We lifted him out of the well using the rope we had used to lower ourselves into the well. We tied it around his chest and pulled him out, and he was taken to the field hospital and treated.

During this time we relieved the English troops and accomplished several important missions, including laying a minefield, shooting down a bomber, and mapping enemy mines. We endured spitfires and the Stuka Bombers.

We were ordered to regroup several miles back and mine a bridge with 500 pounds of TNT. The two men who were left behind to blow up the bridge gave their lives to complete this mission.

We also laid a mine field between a road bridge and a railroad bridge. We endured five days and nights of solid rain, which mercifully stopped on the sixth morning. Lofty and I were assigned to guard the mines. During the time we were guarding the minefield, a GI from the rear joined us. He had gone AWOL from his unit because he wanted action. While we were waiting six days for the attack, we all wondered whether we would see home again. We all did a lot of thinking and praying except for this GI, who claimed to be an atheist.

The enemy attacked at 10:00 am with infantry and tanks. Our artillery was several miles behind us, shooting at the enemy tanks. We were a mere 100 yards from the enemy and the shells were falling on us as well as the enemy. This shelling went on about 30 minutes before several of our light tanks appeared. However, we were knocked out immediately. My squad suffered heavy casualties. I took a hit behind my left ear from a small sliver of shrapnel the size of a needle. The atheist suffered a hit to the back of his head and he shouted to the Lord over and over, “Oh Lord, don’t let them shoot me again!” As I suspected, there are no atheists in foxholes.

The enemy infantry attacked while I was on a machine gun. An incoming artillery shell hit very close to me. The concussion dazed me as I lay on the railroad tracks bleeding from my nose and ear. Two enemy soldiers approached and stood over me. One tried to shoot me and the other kept pushing his gun away so he would miss me. Oh, how I prayed: Lord, let me see my mother one more time, then take me if you will. Suddenly, my mother’s face appeared before me with a look of kindness, her slightly wrinkled brow and upturned lips in a slight smile of understanding. The Lord prevailed. My life was spared. The enemy soldier stopped trying to shoot me as I lay on the railroad tracks.

The enemy soldiers told me to run to their Panzer IV tanks on the road about 100 yards away. Our artillery was firing at these same tanks from their vantage point a mile away. High explosive shells were exploding all around with shrapnel filling the air around me. I made it through with help from above. As I walked past the atheist, he was still praying to the Lord for help. As I reached the tanks, I passed under the muzzle of its 75 mm gun as it fired. The blast threw me over backwards, my nose began to bleed again, my hearing was half gone, and my eyes felt like they had been plucked out and put back in again. I got up and saw one of my men lying dead beside his machine gun. He had been shot in the head. His brains were oozing from the bullet hole and dripping on the ground. I went on along the tanks knowing I would have to walk through the mine fields we had just laid. The mines were buried just under the surface of the ground so as not to be seen. Somehow, I made it to the other side without setting off a mine. I had help from above. One of our men took a hit through his buttocks; I never saw him again. I don’t know if he made it out of the war alive.

Wherever I looked I could see the dead and wounded. We were one platoon of 36 men defending a mine field to hold back the enemy attack of a company of infantry and a half a dozen tanks. Our half-track driver’s foot was shot off above the ankle. I learned after the war that the Germans took him to their hospital and treated his leg. When he recovered enough to travel, they repatriated him home through Spain. Another man lay dead in a ditch, his canteen protruding from his body.

After an hour of trading artillery fire with our troops and wondering if we would survive the incoming shells from our troops, the German tanks and infantry broke through the mine field. Lofty and I were loaded on a supply truck and taken to the city of Tunis, Tunisia.

Taken: Prisoners of War

Tunis

On December 10, 1942, the few of us that survived were taken as prisoners of war. We were loaded on a truck and taken to Tunis where we were housed in a large horse barn. German doctors treated those who were most injured; I did not need more than a look see, so I remained at the barn. We joined a number of English soldiers who were captured in an earlier battle. They told us that we would be searched for souvenirs like watches and rings. I had an oversized piece of bread like a hamburger bun; I broke it open, removed the strap from my watch, and placed the watch in the bread to look like a sandwich. I put my Holland High School class ring in my mouth. While I was being searched I took a small bite of the bread and chewed it, trying not to swallow. I passed inspection. The class ring survived the war, and I will save the story of the watch for another time. We stayed in the barn several days, sleeping on the concrete floor. We were given water to drink.

Our first day in the barn, armed guards herded a group of 25-30 civilians past the barn. Each person carried a shovel. About an hour later we heard machine gun fire. We didn’t know what happened, but we did not see the civilians return.

The next day, an officer and two armed guards entered the barn and selected a dozen prisoners to go with them. Lofty was one of them. Before he left, we said our goodbyes, believing that this would be the last time we saw each other based on what we saw the day before. He was given a shovel and marched away. As the day wore on, we listened for gunfire. Late in the afternoon, Lofty and the others returned to the barn! You can’t imagine the extreme joy I felt at seeing my friend again. He recounted his day, describing how they spent the day digging bomb shelters around the headquarters command building.

On our third day in captivity, we were put on a plane and flown over the Mediterranean Sea. Bad weather forced us to land in Sicily where we were turned over to the Italians.

Italy

We were put in a cell approximately 20′ X 20′; the ceiling was 20′ high, and the floor was covered with straw. We had room to sit but not to lay down. There was a small window near the ceiling. Two guards stood outside of the two two-foot-thick steel barred doors on two walls. Because there were no toilets or water, dysentery was a problem. We urinated through the bars in the doors, risking the bayonets of the guards. We stepped back sharply to keep the straw on the floor and to protect our private parts from the guards’ jabs! We hadn’t eaten for three days, except for one small piece of bread.

On the morning of our third day in the dungeon, we were transported to a POW camp. We were placed on a train bound for Palermo, and were each given one hardtack cracker to eat. We arrived in Palermo in the early afternoon, where we marched single file through the station. We exited on the other side and were surprised to find ourselves in a public square. It was filled with row upon row of 10-12 year old boys, each of whom had a wooden gun. The end of the rows filled with people shouting in Italian, unintelligible to us. We were forced to walk down each row. The people on the end of each row spat on us and tried to put our eyes out with their fingers. Finally, we were loaded on street cars and taken to the edge of town and loaded onto trucks that would take us into the mountains and to our camp. All along the street car route, people lined up to shout and throw rocks at us. Windows broke and glass flew, cutting us.

We arrived at Camp 98, located in the small village of San Giuseppe Jato, located in the Province of Palermo, in Sicily. We soon learned to name it 98 degrees worse than hell. We were quarantined for 30 days before moving to the permanent camp. Here, row after row of tents lined the mountainside. The tents were minimalist and cold, with hard clay floors and no straw to offer cushioning and no heat. Each GI was issued one small blanket, which only covered me from my knees to my neck, leaving much of my body in contact with the cold, hard clay ground. We relieved ourselves in a slit trench that was just outside of the tent, but if we ventured out after dark, the guards would shoot. The commander told us to shout Ronda La Treina and the guards, apparently hard of hearing, would no longer shoot when we went outside to the bathroom. The camp doctor was available to see anyone who was sick, but he didn’t have any medicine to offer us. A week into our time in the camp, Lofty had a case of the “GI’s,” and the doc placed him in the “isolation” tent—with 30 other men. Even though Lofty’s stool changed from loose to firm in a few days, he was confined to the isolation tent for 30 days.

It was December in the mountains and very cold, so we would double up at night, shivering under two too-small blankets on the cold, hard, bare ground. Seventy or 80 of us shared a tent, and every night at 10:00 the guards would check the tent, counting us by hitting our cold feet. We cursed—the guards could clearly understand some English! They would get distracted and excited when they only saw three feet sticking out of the blankets, and would lose count and have to start all over.

We ate once a day at 5:00 pm, dining on one piece of bread and a dixie cup of watery soup. The senior American and British NCOs rationed out the soup; as the Senior Yank, I had this job. Each tent received one boiler of soup to dole out. Everyone would place their cups in rows on the ground. As the British NCOs and I poured the soup, people moved their cups around, trying to get more soup. When the boiler was emptied, we counted pieces of bone and macaroni and recorded the amounts; everyone received one piece of bone and seven pieces of macaroni. We would pulverize the bone with two rocks and lick them clean. We were always hungry, and learned to keep a small stone under our tongues to help satisfy the hunger pains.

One day, I made a trade with a guard—I gave him a shoe string and he gave me half of a cigarette. The fellow next to me was very sick and offered another trade—he would give me his soup for the half cigarette. What a strong hold cigarettes have on the body! He died later that night.

Several days before guards told us when we would move to a permanent camp, I came down with jaundice. My urine turned dark, like black coffee, and my stool was grey. After seeing what happened to Lofty when he was sick, I avoided telling the doctor. I knew better. I lost my appetite and couldn’t eat my soup, and thought back to the ill man who traded me his soup for that half cigarette.

Meanwhile, the doctor said that anyone in isolation could move to the permanent camp if they didn’t have dysentery. They all needed to produce a healthy stool to pass the test. Everyone in the isolation tent knew that Lofty could produce healthy stool, so they asked him for a sample. Lofty had recently gone, but agreed to try and produce more. The GIs gathered sticks to secure their piece of the sample, and Lofty headed outside to the slit trench. After much grunting and straining, Lofty produced a small stool. In their eagerness to get a piece of the stool, the GI’s took all of the stool and Lofty had to borrow from someone else to pass the test. He bore a sore behind from everyone clamoring for their samples, and was a hero to the camp when upwards of 30 men passed the test and were allowed to leave isolation and travel to the permanent camp. We thought that the permanent camp could not be as bad as this camp!

I hadn’t eaten for three days because I didn’t have any treatment for what was clearly hepatitis. I, too, was hoping that things would be better at the next prison. We were all loaded on trucks and transported to Palermo, where we were transferred to a ferry boat to cross the Straits of Messina, and then put on a train for our next stage of the trip to somewhere in Italy. We each received six hardtack crackers for the trip. We were loaded in “40 & 8” boxcars. They were called that from World War I, because they could hold forty soldiers and eight mules. The doors were locked and we had two small window-like openings on each end of the ceiling in the cars. It was very crowded, with approximately 70 of us in each unlit car. The cars did not have toilets, and had about six benches for people to sit on. We had limited access to water—one pail a day for three days. We arranged the benches on one end of the car, and used the other end as a toilet. We took turns sitting on the benches. At this point, I was on my fourth day without eating because of my hepatitis, which took away any desire for food. I was very weak and nearly lost the will to live. I crawled to the end of the 40 & 8 and lay under a bench so I wouldn’t be stepped on. I lay there for three days and nights. When we arrived at the POW camp, it was my seventh day without eating. I still had my six hardtack crackers.

The POW camp known as Camp 59 was in Servigliano, located in the Province of Fermo. We arrived at night. I was so weak that I had to be helped out of the 40 & 8. I heard a voice say, “How you doing, Yank?” I looked up to see an English captain. “I’m a doctor.” I was elated. I was sure he could help me. He made sure I was placed in a barrack—a real barrack this time—dedicated for the sick. I would later learn that these facilities were military facilities from World War I. In the morning, he examined me and confirmed my diagnosis of hepatitis. He said there was a serum that the Germans had developed that could help me, and he would try and get some. He was not the only English healing professional at the camp—another medical doctor, a dentist, and two chaplains had all been captured in Libya in January 1942 and were now all at Camp 59.

Two more days passed, and I was still not eating. Back in Camp 98, we heard rumors of Red Cross food parcels, but in our 30 days there, we didn’t see any and thought it was a bad rumor. I learned from the doctor at Camp 59 that it wasn’t a bad rumor—this camp had the parcels, Red Cross food boxes from International Red Cross in Switzerland. They had both English and American parcels. The doctor was trying to get me to eat and gave me some raisins. I wondered where he got them. He told me that when I received my food parcel that I should trade my cans of food for raisins which would be better for me instead of food that may have fatty content, which is a no-no for hepatitis treatment. I ate nothing but raisins for six weeks.

On the third day at Camp 59, I received good news. The doc was able to get the serum for hepatitis. It was injected in my arm vein every other day. Within five days the yellow of my skin began to disappear. After 10 days, my jaundiced appearance was gone, and I began feeling better: I started thinking about food, my eyes and skin started to look normal, and my urine and BM color (which I never thought much about) improved. My urine went from coffee color to normal and BM from grey to normal color brown. What a beautiful sight!

After the war was over and I was home again, I mentioned the serum I had been treated with to a doctor friend. He told me that the serum was known and taught in medical school, but that it had considerable side effects. It was a 50% cure and a 50% kill chance and was not perfected at that time. It was tested on humans.

I was the lucky survivor.

Time passed slowly and I was always hungry. I kept a small pebble under my tongue to keep my mouth moist. It helped ease the hunger pains. The POW camp routine was hard to do, and I was always concerned about making it back home. One day we were told that we would be given two shots ten days apart. The two English doctors would administer them. Armed guards were all over the camp making sure everyone would take them or be (literally) shot. Two armed guards also made sure the docs didn’t let anyone get by the docs. Because the doctors themselves didn’t know what kind of shot they had to give us to, they told us we should avoid walking fast after getting the shot. They advised us to sit in the shade for half an hour or until we felt okay; since they didn’t know what was in the shots, they thought this advice would keep us from passing out.

Some didn’t listen and suffered the consequences.

Some of the great things the two docs did for those in desperate need of medical help required medical instruments and a fully-equipped operating room, but this was not possible in a POW camp. I witnessed a number of attempts to save lives in the camp while I was recovering. I was in a makeshift room set aside from the room reserved for those needing medical help. In that room there was an English soldier in need of a blood transfusion. One doc took blood from the other doctor, using a razor blade to make a small incision in his arm. They drained this blood into a glass. The doctors had placed a small tube in the patient’s arm, and positioned a small funnel at the end of the tube.

They slowly fed the blood into the funnel and it traveled up the tube and into the patient’s arm. He died the next day, and the doctor who had given blood developed an infection in his arm that almost cost him his life.

Another case involved an attempt to save a soldier’s foot, which had been wounded by shrapnel from artillery fire. He had a large area of flesh blown away and the wound would not heal. They attempted to graft skin onto the wound. Because there were no proper instruments or antiseptic available, they used a small pin to lift skin up from the patient’s arm and cut it off with a razor blade, then place it on the edge of the wound, hoping that it would grow in place. This attempt was repeated over the entire edge of the wound. Previous attempts to graft skin and this attempt did not take. The patient’s arms showed hundreds of scars from the attempts to get small grafts of skin to grow on his wounded foot.

When Doc released me from his care, Italian guards assigned me to a barrack and bed number. I could hardly believe that we had beds, with a wooden frame, double-high, and with slats across to support your body. They came with one blanket and one bag with some straw for a mattress. This was utopia compared to Camp 98 in Sicily. The barracks also had electric lights that were on all night so we could be seen. The camp was surrounded by a ten foot tall wall, two feet thick and topped with broken glass. Guard shacks were positioned every 150 feet along the top of the wall, and a shallow ditch ringed the wall, about 10 feet out. We were told that if we crossed the ditch guards would shoot. This turned out to be true. It happened close to me; I found the bullet. It was a dumb-dumb. Geneva Convention rules do not allow this, but these well-meaning rules can’t always be enforced. All is fair in love and war.

My assigned day to draw a food parcel was Friday—every two weeks I would go and get the seven-pound English parcel. To have a small bite to eat with our watered down soup each day we would have a food partner and split a parcel each Friday. To get our parcel we filed past a small window in the wall and a guard would open the package and proceed to puncture each can with a double-pointed claw hammer. This was done to prevent food hoarding for an escape. Even a two-ounce tin of cheese was punctured, even though it wouldn’t spoil.

The English parcels consisted of:

• 1 tin of tomatoes, 12 ounces

• 1 tin of vegetable soup, 1 pound

• 1 tin of apple pie, 1 pound

• 1 box of raisins, 1 pound

• 1 box of tea, 8 ounces

• 1 tin of cheese, 2 ounces

The American Red Cross parcels were nine pounds, and included almost all of the same foods as the English parcels except for a can of lemon extract. It was so potent that one swallow was enough. No one wanted it. Then one day we found out if we put a small amount of water in the can and sealed the can, in a minute or so it would explode with a loud BANG! For a couple of nights, making and throwing lemonade bombs under the guard posts on the wall was fun; this came to a abrupt end when the guards started shooting into the barracks.

I traded my parcel for raisins. Following the doc’s orders, I ate raisins for the next six weeks and it helped a lot. After that it took years before I could eat a raisin again.

After a couple of months of getting a food parcel every two weeks, the war was going against the Germans and the Italians. We were told that everyone would be given a parcel every week. This gave me seven pounds of food instead of three and a half each week. To this day, sixty-three years later, I can’t stand seeing food wasted, and I eat all of the food on my plate. I still have too many memories of starving. I weighed approximately 160 pounds when I was taken prisoner, and at the time of escape I weighed about 100 pounds. Only the additional Red Cross package, with a full seven pounds of food a week, kept me going.

Because the two-ounce tin of cheese would not spoil, it became our monetary system. Each tin of food had value of so many tins of cheese. Each day those who received the food parcel would trade their food tins for cheese because it would not spoil. Each day we would shop for a tin of food with our cheese tins. This became our bartering system with cheese as value:

• One 8-ounce tin of tomatoes = 1 tin of cheese

• One pound of vegetable soup = 2 tins of cheese

• One pound of apple pie = 5 tins of cheese

• One pound box of raisins = 3 tins of cheese

• One 8-ounce box of tea = 2 tins of cheese

Escape was always a topic of conversation. Tunneling was the option. A tunnel was begun under a barrack. After several weeks of digging, it was completed. During this time a group was formed to be actors and would be giving a play. They would practice and would walk around the camp telling the guards it was being given for them. What the actors would really be doing was waiting for a stormy day, which finally came. Eleven men entered the tunnel then the twelfth man, who was new in camp, tried to enter and got stuck partway in the tunnel and started shouting for help. Because he was a new POW, he had not lost enough weight to fit into the space. The commotion attracted the attention of the guards, who quickly ended the escape. Punishment was doing time in the dungeon.

The dungeon was a hole in the ground less than six feet deep and less that six feet square, with grating over the top. Lofty, who is taller than six feet, was put in the dungeon for seven days because he was late for morning roll call. Blowing wind would send dirt through the grating, guards would walk over it sending down more dirt, and rain would make the hole muddy. Each day we would stand by the fence that separated the torture area from the rest of the camp and shout encouragement to those in the hole. When the guards got tired of this they would rush the fence and force us away. After seven days Lofty was taken out to the main gate of the compound where he passed through and made a derogatory comment. The guards turned him around and put him in the dungeon for seven more days. It was during this time that he almost lost his sanity. To combat this feeling he would sing, count sheep, recall his mother’s cooking, spell words, and anything else that would help him remain sane.

After receiving the shots over my heart area, I fell ill several times and was placed in the makeshift sick room. When your fever broke, you would be discharged, even if you were very weak. That summer I was admitted three times. The last time I thought if I could stay longer I could gain some strength back. Lofty would come every day and visit through the window next to my bed. We talked about my idea, and he said he would bring a hot drink just before the temperature check at 3:00 pm. By sipping the hot water, I would raise the temperature in my mouth and fool the temperature check. It worked great and Lofty’s loyalty and promptness kept me there three weeks. I would keep the hot drink under my blanket during check time. But one day I put the hot drink on the floor, though I don’t know why. On this day, two docs took temperatures and when they came to my bed they approached, one on each side, and pulled my blanket off looking for the hot drink. They had been tipped off by a snitch in the room. The next day, I was sent back to the regular part of the camp. I was much stronger through the efforts of my buddy Lofty. He is one of the best people I have ever know, very trustworthy and loyal. To this day, 64 years later, we still keep in touch and occasionally visit each other.

The camp commandant used “snitch” tactics often. If a new person was put in camp, he was treated with suspicion because he was too heavy compared to the rest of us. We were not fooled. They were usually removed after two weeks. One “snitch” was so obvious that camp guards had to rescue him from the prison population.

The Escape

Time passes slowly in the camp, and I was always hungry and losing more weight each day. I was close to 160 pounds when we were captured on December 10, 1942. It was now September 14, 1943. Around 10:00 that night, the English doctors spread word that a troop train would take all 1,200 POWs to Germany, leaving at 6:00 am the next morning. Upon hearing this news, we started a riot, breaking the gates in the wall. The guards started shooting, and many were wounded and some died. Lofty and I ran to a water well in the field, about 100 yards away, bullets zipping by the whole while. We stayed behind the well until they stopped shooting at us, and noticed another wall with a gate about 75 yards away. We made a dash for it and the shooting started again. We crashed the gate with bullets striking the brick wall around us. We kept moving until daybreak the next morning, and then hid all day until dark. We felt great for the first day out of the POW camp, little knowing that we would be running and hiding for nine months before passing through the frontline to freedom.

The second night we followed the ridge up until daybreak and hid in a wooded area. About mid-day, a boy herding sheep found us. He went and got his dad, who gave us some cheese. We stayed there several days. Then the boy gave us some cheese and told us his dad had gone to a large city. He sure did—and when he returned, he brought back a truckload of Germans to catch us. There was a small cliff rising out of the woods about 50 feet, covered with brush and small trees, and what appeared to be a ledge to hide on. We started climbing and as we almost reached the ledge, we realized it was a path. At this moment a German came running past with his gun, yelling for Schultz. If he had glanced down, he would have seen us. We were lucky. After a couple of hours they left and we stayed hanging on to a tree until dark, then we climbed onto the path. We followed the path and the ridge until morning, and then hid in a sugar cane field until dark before continuing up the ridge until it ended at a small village. We crawled across an open field on our hands and knees because the moon shone so bright and we were afraid of being seen.

We were finally at the village. As daylight approached, we found a place to hide for the day, and stayed in hiding for several days. We had not eaten for three days and were very hungry. The village seemed quiet so we decided to go to the edge of town and ask for food. So with our hands raised to show that we did not have guns, we went down to the village and on a short side street with four houses, we knocked on the doors of three houses. All three quickly closed their doors in fright. At the fourth house, a lady answered the door and looked at us. We were not too presentable. We made signs of hunger and she shook her head that she understood and then gave us a loaf of bread and some cheese. We made signs of thanks. Our first attempt at begging was a success. Little did we know how many times this would be repeated in the next nine months. We were always moving around to avoid being recaptured.

While hiding near a monastery located close to Montefalcone Appennino in October 1943, we were befriended by the monks who would bring cheese and bread to us each day. One day a woman and her 16 year old son from Montefalcone came to us, bringing food. They did this for several days, as we became better acquainted, they asked us what we did in America. I said I was an engineer, and Lofty said he was a rancher. They continued bringing food and then one day the boy came alone, with a book, paper, and a pencil. He showed us ten pictures in the book that he had to reproduce freehand for an art course in school. We told him we could not draw. He said, “Engineers can draw. If you don’t, I will tell the Germans where you are!” Lofty advised me to tell the boy that I would draw the pictures to buy us some time to figure out what to do. I told him I would try, and it would take me a couple of days. After he left, I looked at the pictures again. One was of a mountain goat on a cliff, another was a little girl with a sand pail on the beach. Out of curiosity, I tried sketching both of these pictures. After several attempts, I discarded them all. Some time later, Lofty looked at the discarded sketches and said, “What’s wrong with these? They look good to me!” With his encouragement, I tried again and sketched all ten pictures. A few days later, the boy came back for his pictures and was impressed with them. I never did find out if he passed his art course. We left the area in a hurry to find a new hiding place.

On October 22, while hiding near the monastery, a fellow contacted us and told us he was a paratrooper and along with a few others was dropped in the area to contact us and others. He said that if we followed the Chienti River to the Adriatic Sea there would be landing barges there to pick us up at midnight on October 24. He said he would guide us to a bridge over the river. We arrived there the afternoon of the 24th, and he told us to wait until dusk and he would return with the others to join us. As it became dusk and our guide had not returned, with darkness approaching, we decided to follow the river to the Adriatic without a guide. After walking for about an hour we met a small group of people. We tried to pretend that we were Italian but that did not work. The two older men said they were English and asked what we were. We said we were American and at that moment the other four of the group started screaming like animals, and waving their arms. We started striking back and the two English men started hollering “Don’t hit them, Yank!” The men were blind and had their tongues cut out in a torture camp.

They were happy because Americans would be picking them up tonight by boat. They were happy that we were Americans. The parents of these kids were politicians and were put to death; the kids were tortured so they could not follow in politics. The two adults had them hold onto a stick so they could be lead along the river.

We moved on and the closer we got to the Adriatic, the more people we could see following the river. Time was running out. It was almost midnight when we came to a fork in the river. We started following the stream we thought was the correct one, but found out it wasn’t. We retraced our steps back to the fork and stopped to rest. We were about 100 yards away from the railroad bridge when search lights at the beach flashed on some 200 yards from us. Then machine guns began firing and we could hear people screaming. Needless to say we made an abrupt about-face and hurried back the way we came when it began to break dawn and we hid until noon. Things seemed to be quiet so we continued on. About four o’clock we were climbing a ridge and were near the top when a German convoy came by, then a couple of English spitfires showed up and made a couple of strafing runs on the convoy. What was left of the convoy moved on. We stayed hidden until almost dark and then went up to the road, where there was a farmhouse by the road. The people were all excited and gave us some bread and cheese, and asked us to spend the night in the barn. We agreed. They showed us a hollowed out haystack to use as a hiding place. If the enemy returned, we could hide there. The next morning we left and figured we would reach Montefalcone by mid-afternoon. Several times we had to hide in the brush as Germans passed. Other than that, we finally made it back to Montefalcone. The monks and people were very surprised that we made it back. They brought out cheese, bread, and wine to celebrate our safe return. They told us that about 700 people had been killed, wounded, or recaptured. To this day I still wonder what happened to the blind boys we met.

Here Louis VanSlooten’s notes ended. The following paragraph has been added by his son Tom from conversations he shared with him.

Skipping forward to the last 24 hours of their year and a half ordeal, they had heard that the Allies were advancing north and were getting close enough that they thought they had a chance to sneak through the German lines and back to Allied controlled territory. It would take them a couple of days to walk to where the Allies were reported to be. On the last night they took refuge in a stone hut they found along a mountain trail they were following. Dad and Luther were dressed in civilian clothes and in Dad’s vest pocket was a Gideon Bible he carried throughout the war. That night he hung the vest on a peg inside the hut, and in the morning fate would have it that he forgot the vest when they set out on their way again. Later in the day, as Dad and Luther were taking a break along the trail a German patrol came up and caught them out in the open. They were in retreat from the Allies, and Dad and Luther looking like locals in civilian clothes somehow managed to keep their cool. The Germans approached them asking for direction to a nearby village. Having spent some time with the locals their command of the Italian language was good enough to convince the Germans as they were no doubt in a hurry to vacate the area. Getting back to the Bible, you see it was an English Bible and it stuck out of his vest pocket enough to see it. Had Dad not forgotten it that morning in the stone hut the Germans would surely have noticed it and they would have been taken prisoner again or shot on site. Dad always claimed that the hand of the Lord was on them that day and three hours later, on June 14, 1944 they ran into a unit of the British 8th army, ending a year and a half of prison, escape, evasion, and severe starvation. On that same day that they made it back to freedom Dad noticed on a distance mountainside a church with a cross steeple and the sun was shining on it. To his final days whenever we would sing the “The Old Rugged Cross” in church it brought him back to that day. It was his favorite hymn.

Louis also shared this memory:

About a year after I was discharged from the service I bought some property and went to attorney Pete Boter to fill out paperwork on my purchase. While it was being typed up, Pete asked me if anyone tried to pick us up. I said yes, but it was German trap to get us all in one place. Then he asked if I would like to hear the other side of my story.

He was with the CIA and helped plan getting all of us out. When the paratroopers dropped in and told of the plan, the fascists picked up on it and told the Germans. The day we would be picked up six landing barges went up the Adriatic coast to pick everyone up.

What a loss of life in trying to get us out.

Afterward

VanSlooten and his friend Shields spent nine months total living and hiding in Italy, primarily in the Marche region. They survived by foraging for food; by the kindness of strangers, who provided shelter, warnings, and food; and by faith in God. They were finally rescued by the British Army in Ascoli Piceno, and transferred to the U.S. Army. According to an article published in the November 1952 issue of General Motors Better Highway Awards, VanSlooten was on convalescent leave in Florida before being transferred to Fort Knox, Kentucky, where he worked with magazine illustrators and learned how to airbrush, a skill that later helped him land a job with General Motors. He was discharged in 1945 and returned to his hometown of Holland, Michigan, where he lived a full life. He married Esther (Huyser) Van Slooten in 1952; fathered three children, Karen, Thomas, and Steven; worked as an engineer at General Motors; served in local government; and farmed blueberries. At the time of his death in 2011, he had nine grandchildren and four great-grandchildren.

Louis VanSlooten, stateside after his escape and very thin from 18 months with little to eat, circa 1944