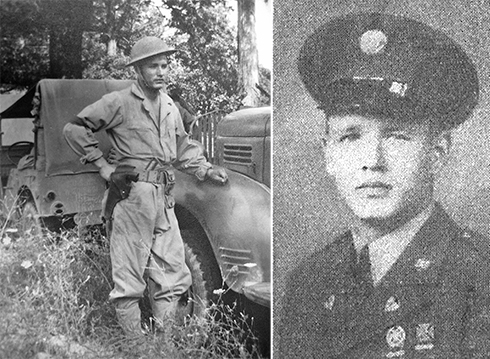

“A portrait of Bertie from an unknown time,” says Jeremy Bones, “but given he looks young, it could be pre-WW2.”

I received an email last month from Jeremy Bones.

He wrote, “I am currently conducting research into my great-grandfather, Gunner Ronald Bones, who was held as a POW in Camp 59. I have noticed that Robert Dickinson, who wrote “Servigliano Calling,” was also in the camp but, more importantly, was in the same battery as my great-grandfather, 237 Battery of 60th Field Regiment, Royal Artillery.”

Indeed, Ronald Bone’s address is one of 20 recorded in Robert’s journal. As such, it seems likely he and Robert were good friends. See “Robert Dickinson’s Address List.”

“My great-grandfather was born on 21st August 1910 in Grimsby and lived in Lincoln his entire life.” Jeremy said.

“I have a number of photos of him in my possession, and a good few are of him in POW camps. I know some of them are from Stalag VIIIA.