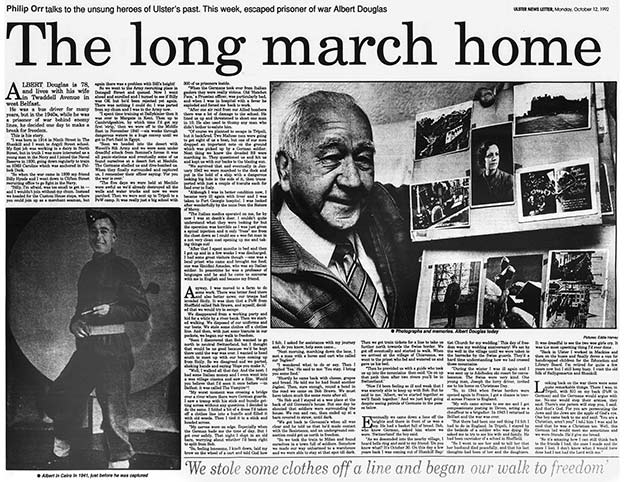

Last September, I was pleased to receive a newspaper clipping from Richard Minshull regarding POW Albert “Paddy” Douglas, about whom I’ve written several posts.

Albert Douglas was Richard’s wife‘s grandfather.

The clipping, published in 1992 in Belfast, Northern Ireland, had been overlooked when Richard sent me a wealth of other clippings, documents, and photos several years ago.

The long march home

Philip Orr talks to the unsung heroes of Ulster’s past. This week, escaped prisoner of war Albert Douglas

Ulster News Letter

Monday, October 12, 1992

Albert Douglas is 78, and lives with his wife in Twaddell Avenue in west Belfast.

He was a bus driver for many years, but in the 1940s, while he was a prisoner of war behind enemy lines, he decided one day to make a break for freedom.

This is his story.

“I was born in 1914 in Ninth Street in The Shankill and I went to Argyll Street school. My first job was working in a dairy in North Street, but in truth I was more interested as a young man in the Navy and I joined the Naval Reserve in 1930, going down regularly to train on HMS Caroline which was anchored in Pollock Dock.

“So when the war came in 1939 my friend Billy Hynds and I went down to Clifton Street recruiting office to go fight in the Navy.

“Billy, I’m afraid, was too small to get in and I wouldn’t join without my chum. Instead we headed for the Custom House steps, where you could join up as a merchant seaman, but again there was a problem with Bill’s height!

“So we went to the Army recruiting place in Donegall Street and queued. Now I went ahead and enrolled and I turned to see if Billy was OK but he’d been rejected yet again. There was nothing I could do; I was parted from my chum and I was in the Army now.

“I spent time training in Ballykinler then it was over to Margate in Kent. Then up to Cambridgeshire, by which time I got my first ‘stripe,’ then we were off to the Middle East in November 1940—six weeks through dangerous waters in a huge convoy until we got to Port Said in Egypt.

“Soon we headed into the desert with Wavell’s 8th Army and we were soon under dreadful attack from Rommel’s forces: it was all panic-stations and eventually some of us found ourselves at a desert Fort in Mechile. The Germans shelled us and dive-bombed us. When they finally surrounded and captured us, I remember their officer saying: ‘For you the war is over.’

Continue reading