Last year I described in a post titled “Robert Dickinson—A Banner Year for Discovery” how Steve Dickinson was gratified to receive fresh information about the circumstances of his uncle Robert’s death. Robert died fighting with the Italian partisans in March 1945.

However, Steve still longed to meet descendants of the Italians who were protective of Robert in his final months of his life.

In 2009—not long after I met Steve—he told me that he had tried to find descendants of Ginetta “Gina” Bauducco, a woman whose family he believed had sheltered Robert in her home on Via Armando Diaz in Gassino, Italy.

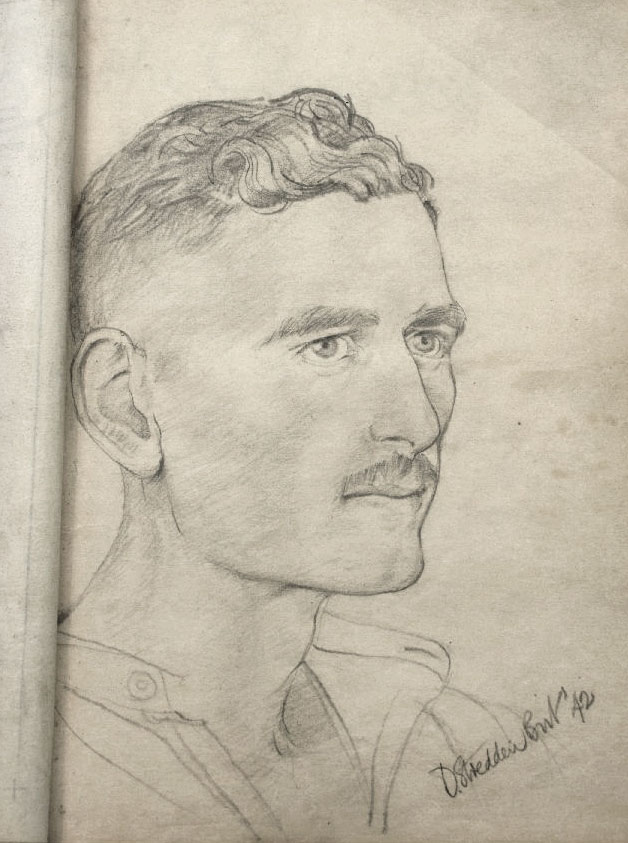

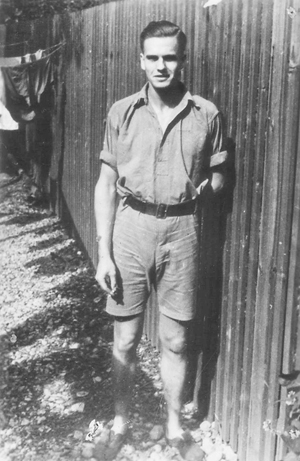

Steve created flyers with information about Robert and a picture. “Spent some time in the village where Robert was hidden and left some of the fliers in various places,” Steve wrote to me. “Several shops, including the pharmacy, said they would put them in their windows. Also, left many in post boxes on Via Armando Diaz.”

Steve’s email address was on the flyer; disappointingly, he received no responses. In 2023 he once more attempted a search, this time with the assistance of a local journalist and a piece in the local newspaper; again there were no responses.

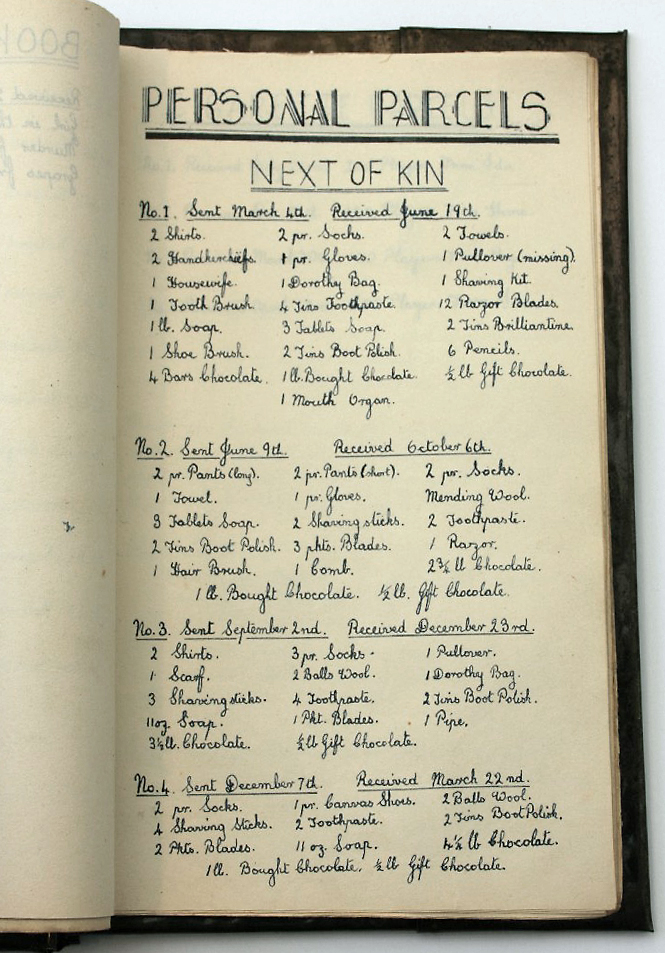

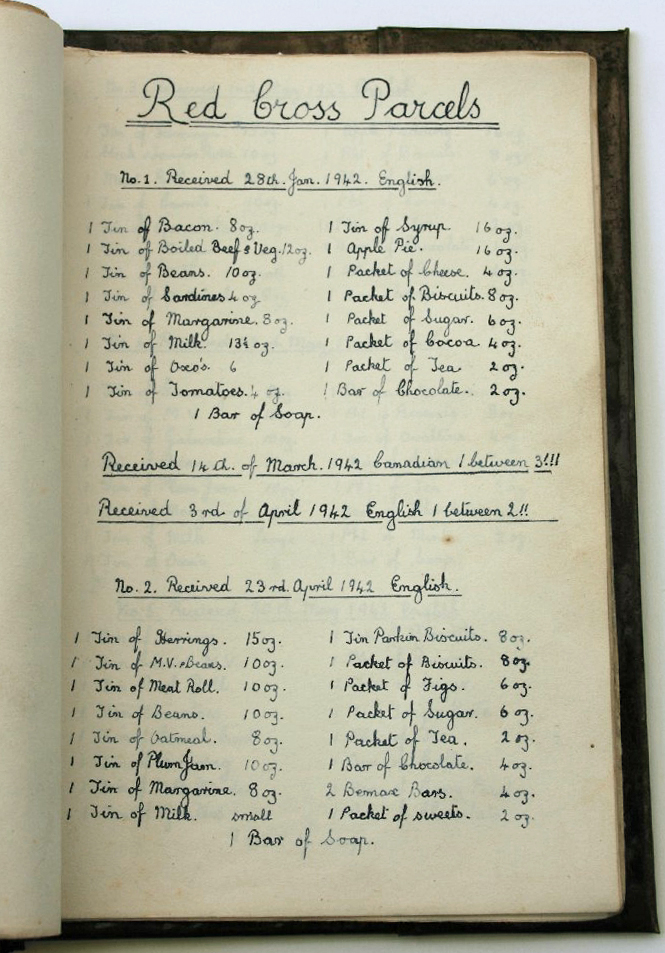

The last camp where Robert was interned was PG 112/4 Turin, where 126 English soldiers were tasked with construction of the Cimena Canal.

Shortly after the Italian armistice was signed Robert and his friend Ronald Dix escaped the camp. The next day they encountered the Bauducco family, who took them into their home.

Continue reading