Robert Dickinson kept a diary, titled “Servigliano Calling,” from the date of his capture by the Germans until six months before his death (November 23, 1941 to September 3, 1944).

Robert arrived at Camp 59 on January 18, 1942, and a year later—on January 24, 1943—he was transferred to Camp 53 in Sforzacosta.

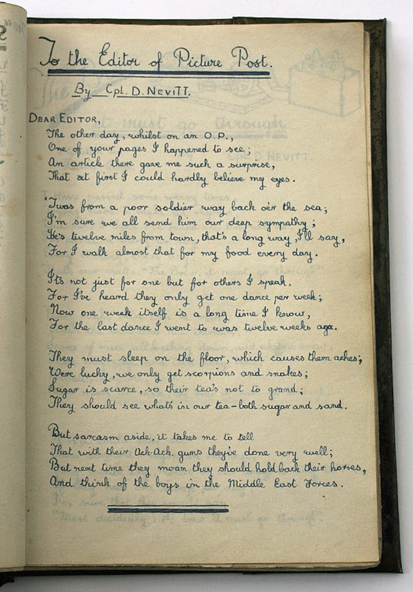

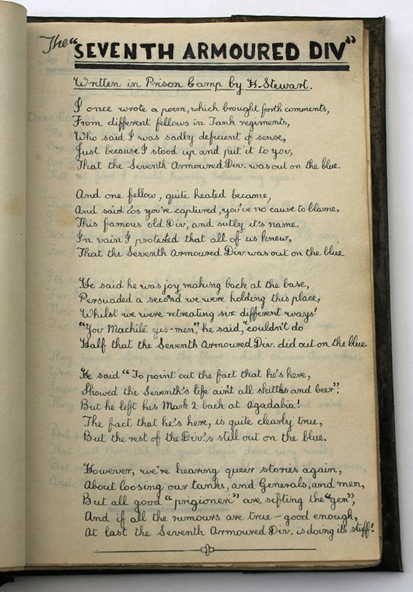

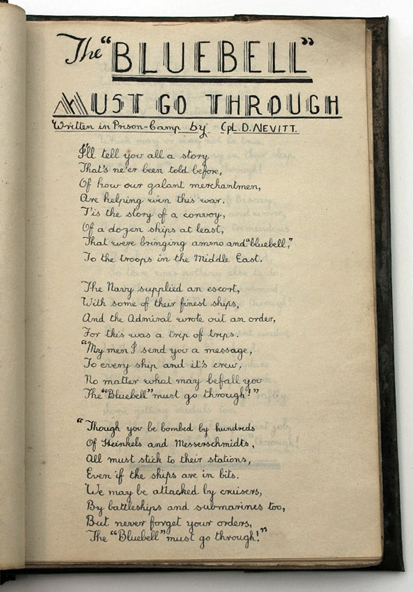

Robert’s log for his year in Servigliano is a fascinating, candid record of daily life and events in the camp.

I first learned about “Servigliano Calling” though e-mails from Robert’s nephew Steve Dickinson in April 2008.

Referring to Camp 59, Steve wrote:

“My uncle spent some time there during WW2, but was later transferred to another camp in Northern Italy. At the time of the armistice he walked out of that camp and fought with the Italian partisans until his death towards the end of the Italian Campaign.

“However, during his stay at Servigliano he kept a diary like many of the POW’s. This was found during renovations in a farmhouse [in Gassino, Italy] where the partisans had been hiding him some time after the war and returned to the family. It details the day to day events in Servigliano, football matches, escape attempts, cooking recipes, poetry, etc….”

You must be logged in to post a comment.