Armie with his youngest son, Dennis, at home in Phelps, Wisconsin. July 1961.

As the youngest of Armie and Eini Hill’s four children, I was affectionately called “the kid” by my siblings.

As a boy, I liked to rummage in my dad’s old Army trunk, which was full of treasures, including his medals, photographs, and foreign coins. I asked questions, but Dad let me know when it was time to shut the trunk and return to the present.

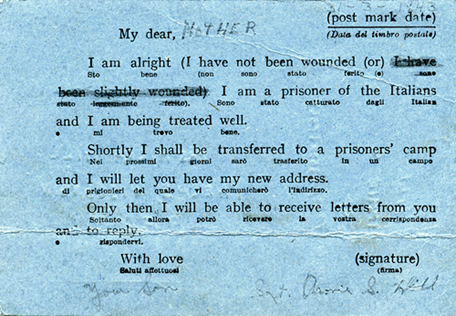

Growing up, I didn’t know much about my dad’s prison camp experience. He rarely talked about it. Once in awhile, he would count in Italian for us kids, “Uno, due, tre, quattro, cinque, sei, sette, otto, nove, dieci….” And he’d explain, “I used to count the men in Italian, in the prison camp, every morning.”

Sometimes he would wake at night crying out, “Who’s there! Who’s there!” And I knew he had been dreaming about the war and being hunted after his escape from the prison camp.

In 1976, when I was in college, I got my dad to tell his story on tape. The taped story began in August 1942, when he and his fellow troops left the States, and ended with his work as a guard at the Port of Embarkation in New York City near the end of the war.

In 1987, my dad again recorded a part of his story for me on tape, this time beginning with his induction in 1941 and ending with his return to the States after the escape from Camp 59. The second tape had new details of his war and POW experiences.

In presenting his story here, I’m rely on these taped accounts, as well as letters he sent home, the notebook he kept while a prisoner, and other documents he saved over the years.

Read Armie’s 1976 interview in these four posts:

“Combat and Capture—Armie’s 1976 Story,” “Recollection of Camps 98 and 59,” “Escape—Armie Hill’s First Account,” and “Armie Hill—A Final Chapter.”

Here are three links to the 1987 interview:

“Combat and Capture—Armie’s 1987 Story,” “A First-Hand Account of Camp 59,” and “Escape—Armie Hill’s Second Account.”