If you type “Feehan” in the search box on this website you’ll see that references to Australian infantryman James “Jimmy” Feehan have occurred in a number of posts. For years has Jimmy struck me as a particular interesting fellow, so I’m devoting this post exclusively to him.

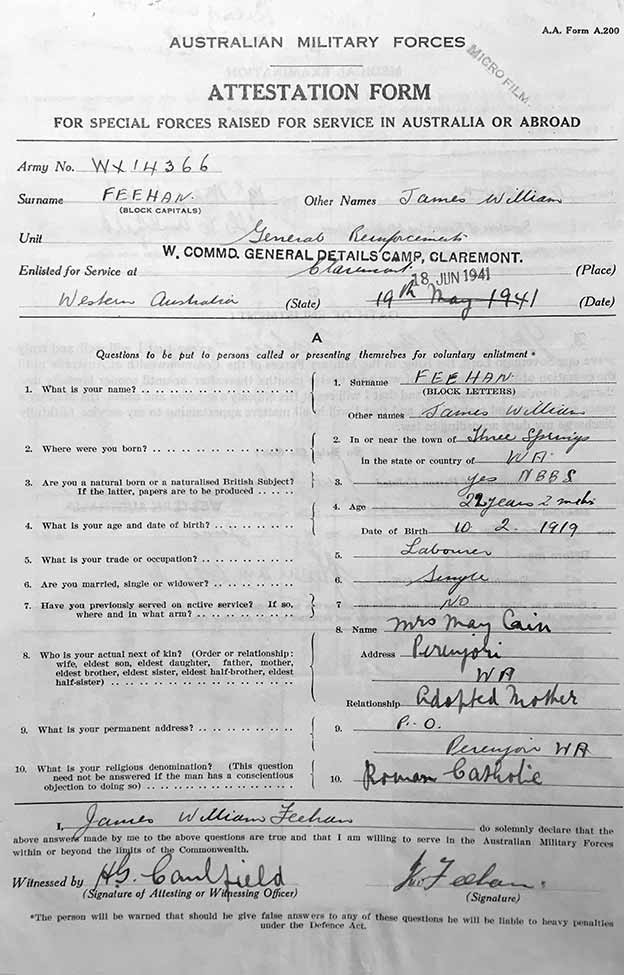

Jimmy enlisted on 18 June 1941 and served in the 2/32 Infantry Battalion of the Australian 9th Division, which saw action in North Africa in 1942. Jimmy’s military record notes he was reported missing in action 17 July and officially confirmed a POW on 22 October 1942.

The Australian War Memorial website has this description of the conflict at El Alamein where Jimmy was captured:

The war in North Africa had become critical for the British forces. In July 1942 Germans and Italians had reached El Alamein in Egypt, about seventy miles from Alexandra. The 9th Division was consequently rushed to the El Alamein area and held the northern sector for almost four months as the British Eighth Army was reinforced for an offensive under a new commander.

The division’s orders for the first attack were issued on 7 July. Moving inland from the coast, the 2/32nd and 2/43rd Battalions (comprising the 24th Brigade) would attack along the ridgeline from Trig 22 and approach Ruin Ridge. The 2/32nd would lead the attack, advancing from Trig 22 to the Qattara Track. The 2/43rd would then proceed towards Ruin Ridge.

The attack began on 17 July at 2.30 am. The 2/32nd captured the Trig 22 and linked with the 2/43rd but the Germans resisted fiercely and counter-attacked with tanks. The 2/32nd suffered heavily: nearly half its number were either killed or wounded and nearly 200 became prisoners of war. The fighting continued for several days.

Jimmy was interned in PG 59. While over 70 Australians passed through PG 59 en route to camps in northern Italy, Jimmy was one of just nine still in the camp at the time of the mass camp breakout in September 1943.

The others were John “Jack” Albert Allen, Thomas David Alman, Arthur George Bell (sometimes known as A. G. Jux), Lawrence Mortimer “Lawrie” Butler, Vaughan Lawrence Carter, Robert Edward Albert Edwards, Ronald James “Jimmy” McMahon, and Leslie Worthington.

Jimmy is mentioned in two prisoners’ accounts of the escape:

Scotsman Thomas Penman shared an account of his escape with his daughter Helen McGregor and her siblings. According to Helen, “ … dad escaped through a hole in the wall along with numerous others. He, Jimmy Feehan of the Australian army, and an unknown soldier were together.”

“The third soldier was shot in the back whilst escaping.* Dad spotted the guards jumping into trucks to chase the escapees, and he told Jimmy to hide only about 300 yards from the camp, believing no one would look for them so near to the scene. They watched prisoners being rounded up, so they made their move and ran into the Italian countryside.”

*Although other soldiers have claimed they were fired on and that some escapers that night were killed or injured, I haven’t come across credible evidence of anyone being killed or wounded by guards during the escape. However, there are statements to the effect that warning shots were fired into the air.

Jimmy McMahon had a different account—of an isolated escape occurring hours or perhaps even days before the mass breakout:

“I suggested to my mates, one Scot and five other Aussies [including Jimmy Feehan], that instead of digging our way out we should try going over the top. We nutted this plan out and thought there would be enough time while the guards, patrolling the wall, were having their halfway talk and smoke, giving us about five minutes.”

The ladder used in this escape was constructed with nails smuggled into the camp by a visiting priest. It’s certainly a thrilling story that one wants to believe!

Jimmy was reunited with the Allied forces sometime around early July 1944. (He embarked Taranto 4 July 1944, but may have crossed the Allied lines some days earlier. He had been on the run in Italy for nearly 10 months.

He was discharged on 25 October 1944.

Home Life—Before and After the War

Jimmy lived in Western Australia his entire life. About 65 kilometers (45 miles) separate Three Springs, where Jimmy was born, from Perenjori, where he lived with Mrs. May Cain, his adoptive mother.

Three Spring and Perenjori are both small towns which today each have a population of about 300–350; they’re located in the Wheat Belt of Western Australia.

Jimmy’s discharge papers show his civilian address as Freemantle, a port city in the Metropolitan area of Perth. By 1985–86 he was living in Maylands, a riverside inner-city suburb of Perth.

Jimmy was married twice. I’ve been in contact over the years with his daughters Maureen Hunter and Pamela Robinson who, as half-sisters, have lived with him at different periods in his life.

Both speak of him very fondly. He was clearly a loving, affectionate father to both.

“[My dad] was a very hard worker.” Maureen said. “ I believe he had a terrible childhood with Mrs. Cain, who used to beat him—so sad.

“His mother passed away when he was very small and he was taken away.

“Mrs. Cain was a very cruel person who treated Dad awful. He was hit and Mum told me that a policeman went to Mrs. Cain’s in Perenjori and told her not to lay another hand on him.”

Perhaps it was his eagerness to escape May Cain’s abusiveness that caused Jimmy to join the Army.

Pamela told me, “Dad lied about his age on his enlistment [form]. At the time the age [for enlistment] was 21 years, and Dad was only 19 at the time, but the following year they dropped the age to 18 years.

“Dad had a stutter, except when he spoke Italian—which was very rare.

“He never spoke of his time in the war. Most of our knowledge came from Mum and stuff that we found out after he passed.”

Similarly, Maureen wrote, “I did not have insight into my dad’s war life until I unfolded things not so long ago. I only wish I knew of these events when he was alive. He was Aboriginal, and I only found that out in the late ’70s. It was all hushed up, and I always wondered why we never met his family.

“My Dad met my Mum as he was working on her parent’s farm in Perenjori. Mum’s name was Ellen Olive Payne. She had separated from her first husband and was staying at my grandparent’s farm.

“He knocked on the door to get a little bowl of fat. She answered. They fell in love. She had his Aboriginality for years. I found out when I was 22.”

Regarding my writing about her father in Camp 59 Survivors, Maureen said “I would love for you to mention his Aboriginality.”

After the email exchange with Maureen, I read online about the “stolen generations”—Indigenous Australian children who were taken from their families forcefully through the Australian government’s assimilation policies, the intent of which was the destruction of Aboriginal society. This was happening from the early 1900s into the 1970s.

The United States had similar programs in the late nineteenth century, taking Native American children from their families and placing them in boarding schools. The U.S. movement seems to have inspired similar policies in Canada and Australia.

Jimmy’s name is included in the Indigenous Service list of the Australian War Memorial.

In 2014, Australian researcher Katrina Kittel wrote to me:

“There are a number of Australian families who are wiser about their veteran’s experience as a POW from extra snippets of information obtained from files that Brian Sims could provide. And they are very grateful for that.

“One of those descendants is a young Australian artist of note, Tony Albert. Tony is a proud young Aboriginal Australian, and is grandson to a Queenslander, Edward “Eddie” Albert. Tony currently works on a commission to design and build a memorial sculpture to Indigenous Veterans in Sydney’s Hyde Park. To be unveiled pre-Anzac Day 2015. I plan to be there.

“By adding a bit more to his understanding of his grandfather’s time as a POW in Europe, Tony is informing the work of this sculpture, and that will be an enduring legacy to not only the veterans, but it also can bring some satisfaction to researchers who dig out some of what the men could not bring themselves to share in voice with their families.”

(Read about Tony and his sculpture, Yininmadyemi, Thou didst let fall, on the website of the City of Sydney, and about Tony’s father Eddie Albert on SBS News.)

Jimmy’s Legacy

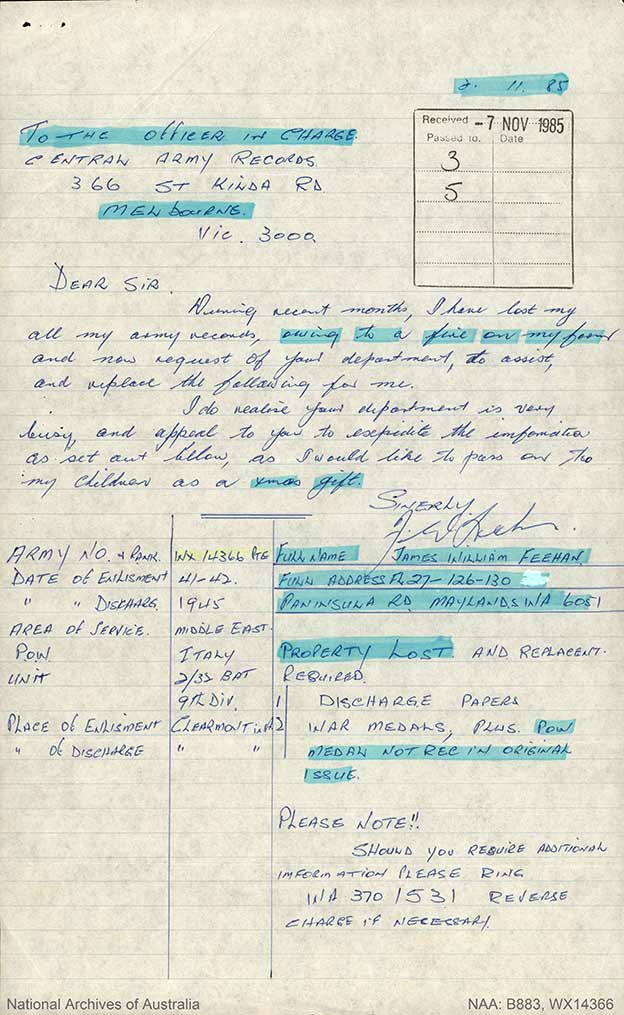

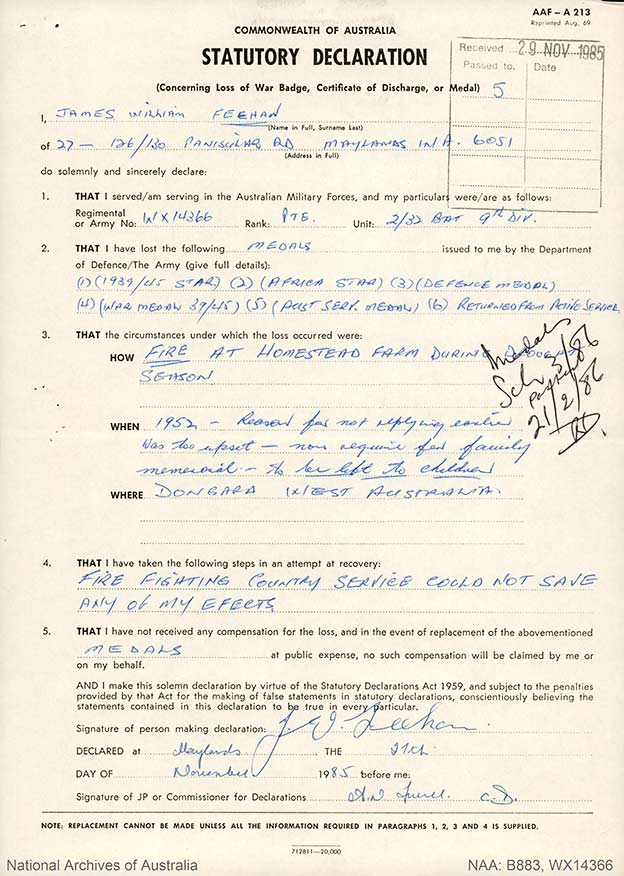

In November 1985, Jimmy wrote to the Central Army Records Office in Melbourne to request a copy of his military service record and replacement of lost medals. There had been the fire at his homestead farm during the drought season, he explained, and his paperwork and medals were destroyed.

The fire had occurred in 1952, and on the form Jimmy noted the “reason for not applying earlier was [that I was] too upset” at the time.

Jimmy added, “I do realize your department is very busy and appeal for you to expedite the information as set out below, as I would like to pass [the requested materials] on to my children as a xmas gift.”

Jimmy’s request became a part of his permanent military record in the National Archives—a sweet testament to his relationship with his children—and his wish for them to remember his service to his country and the Allied cause long into the future.

Today Jimmy’s name is engraved in stone—along with the names of more than 36,000 other Australian POWs—at the Australian Ex-Prisoners of War Memorial in the Ballarat Botanical Gardens, Victoria.

The War Memorial website offers this description of Jimmy: “FEEHAN, JAMES WILLIAM … Held Campo 59 escaped reached Allied lines RTA [returned to Australia].”

Jimmy died 4 November 1992 at the age of 70. He’s buried in Lakes Lawn Cemetery, Mandurah, Western Australia.

I’m grateful to Katrina Kittel for directing me to Jimmy’s military service files, and for her generosity over the years in providing me with information about Australians who have passed through PG 59.

This is Beautiful.

thank you.

Maureen Hunter ( Nee ) FEEHAN.

James William Feehans daughter.