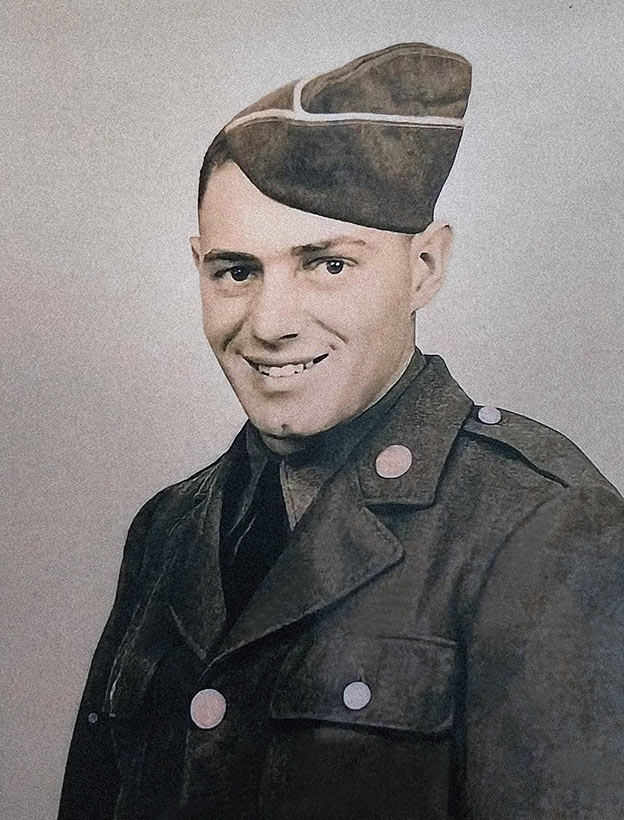

More than a decade ago I wrote five posts about American prisoner of war Willman King on this site.

Willman, from Detroit Lakes, Minnesota, was inducted into the service in October 1941. After training in the U.S., he was sent overseas. He participated in the November 1942 Allied invasion of North Africa, and the following month was captured in Tunisia. He was interned in PG 59, from which he escaped in September 1943. Like many other escapees, Willman was cared for by local Italians.

Willman’s son Joseph was my contact when I wrote those five posts. Confident that Joseph and I had exhausted all the material there was to share about Willman, I didn’t expect to hear further from Willman’s family. So I was surprised in September to hear from Rena Buhr, one of Willman’s daughters.

”I am preparing to visit Italy in early November,” Rena wrote. ”I would love to have any insight into a visit to Camp 59—what to expect and amount of time to explore.” We began an exchange of emails. She used the word “pilgrimage” to describe the trip.

“It feels like the beginning to a hopefully deeper discovery of what [this chapter of his life] was like for my father. He died when I was 21. I was very close to him, but I realize I was too young to comprehend or inquire into what that time was like for him. I have spent my adult life intrigued and deeply moved by what/how the time [he served in combat and as a prisoner] shaped him as a person and by extension how it affected/shaped me.”

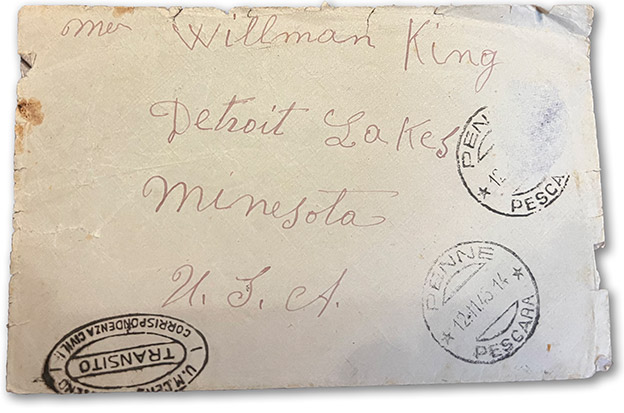

In going through letters and documents from her father’s time in service, Rena found a letter written in Italian.

The three-page letter, written in November 1945, was from Vincenzo Giancola, an Italian who lived with his family in the little village of Roccafinadamo.

Roccafinadamo is about 115 kilometers (71 miles) south of Servigliano.

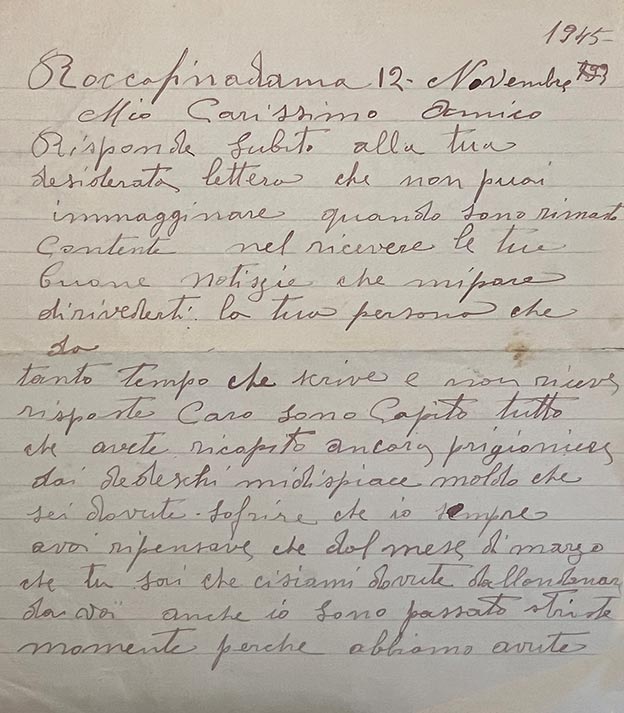

The letter was difficult for us to translate, so I asked my good friend Gian Paolo Ferretti for help. Two days later Paolo sent us his translation.

He mentioned the letter had many grammatical errors and was written with sparse punctuation. “Vincenzo … used the phrases a bit differently than we would write today,” he explained. “I tried to translate maintaining the most fidelity possible … some phrases might sound bad in English, but [they’d sound odd] in Italian, too.”

I’ve added a few of my own notes in brackets.

Here is the letter:

Roccafinadamo, 12 November 1945

My dearest friend,

I am immediately answering your cherished letter. You can’t imagine how happy I am to receive your good news—it seems to me a long time has passed since I saw you, and I had written to you [since then], but [until now] hadn’t received an answer.

My dear [friend], I understood that you had once again fallen a prisoner to the Germans. I am so sorry that you have had to suffer. [Please know] that I constantly reflect on that [fateful] month of March [when you were recaptured]. You know that we had to move away, too. In sad moments I think of the spy who I had kept in my house, [and] all the days Germans were around us—[and were at any time ready] to grab us. Finally, all my family went into the mountains. We had to abandon our cultivated fields, so we ran out of money and resources, but I thank God that he saved us. And I’ll let you know that four of us here were shot, and they were the ones who mistreated you and were the ones who spied on us, and so God made this happen to them. [They were shot] by the Germans by mistake, and we thank God that we were saved.)

My dearest friend, I was pleased to learn that Giacomo has returned to America. [The Italians often called the POWs by the Italian version of their English names. Hence, Vincenzo refers to escapee James (or Jim) as Giacomo.] Let me know if all your other fellows are back, because as soon as I crossed the [Allied] front I wrote to everyone. I didn’t receive any answers, except for yours.

Can you do me the favor of letting me know something [about the others] and say hello to [them] and send me their correct addresses.

Dear “Ulielmo,” [ … Paolo tells me that William in Italian is Guglielmo, and so Vincenzo calls Willman “Ulielmo” … ] you will have to excuse me that I couldn’t have treated you better than the way I treated you. But you know that I am poor, and I had nothing better [to offer] than the love I feel for you, which is better than [the love one feels for] a brother. And my child Donato also feels this way—when he saw your letter he kissed it, remembering your singing “La Campagnola.” [“La Campagnola” is a folksong still popular today in Italy.]

Dear friend, you know how happy I would be if I could come to see you in America. Let me know if it is possible for me to come to America.

My dearest friend, in this letter I am sending my photo. I would like yours, if you would be pleased [to send it to me]. I await your next response. Please be aware that I continue to remember [with affection] only you and your fellows.

Say hello to your family. [I send greetings] from my family and I greet you very dearly as your friend,

Giancola Vincenzo

Roccafinadamo

Province [of] Pescara

Paolo sent me a link to a short article by Claudia Piermari describing a Nazi-Fascist massacre near Roccafinadamo. This massacre is the incident Vincenzo mentioned in his letter.

According to Claudia Piermari :

The four men (Michele Marini, Di Donato Isidoro, Regolo Antosa, and Astolfi Corrado—known as Corradino) had been captured by the Germans while they were working in the fields, on a farm between Roccafinadamo, in the municipality of Penne, and Arsita, because they had helped some young partisans. According to the reconstruction made by [the partisan band] Ammazzalorso after the war, in the area of capture the gang led by vice-brigadier Corrado Roberto operated, the so-called fourth sector, which gathered anti-fascists from various municipalities in the interior, from the Vomano valley to the Fino valley, and which operated in close contact with the Ammazzalorso gang. The four men were anti-fascists and collaborated with the partisan formations. Six days before the shooting, Di Donato was working in the fields with his 15-year-old son Raimondo and Michele Marini, whom he had given hospitality to (since he had just returned from the Russian campaign), while in the nearby fields there were Antosa and Astolfi. About a hundred meters away from them, a firefight took place between a group of partisans and two Germans who had emerged from the curve on bicycles. The partisans began to flee, and in their escape they asked the four farmers for water to drink and to wash the wounds they had incurred while escaping through the brambles and barbed wire, then disappearing into the fields. The Germans saw the scene and arrested the farmers, as guilty of having helped the fugitives. Only Raimondo Di Donato escaped arrest by running away. The four men were taken to Teramo and imprisoned. On June 9, 1944, the four were taken by the soldiers of the “M Battalion” on the orders of the German command (the order delivered by Catucci Giuseppe), taken to Montorio al Vomano, and were shot behind the cemetery wall in retaliation. The bodies of the four men were thrown into the common grave, reported as unknown by di Isidoro, and buried in Roccafinadamo.

Fascist Battalion “M” and the notorious German Brandenburg Regiment were implicated in the 1944 execution of six Allied POWs in the Comunanza village cemetery. (See “An Execution at Comunanza.”)

On the following day Rena sent me a scanned photo of a man. On the back was penciled “Ricordo di Giancola Vincenzo” (for remembrance of Vincenzo Giancola).

On October 15, I wrote to Rena: “Are you ready for more exciting news? After the war, Italians were encouraged to apply for compensation for assistance they gave to escaped POWs. A set of cards indexing these claims is online at the U.S. National Archives (NARA).

“I just found the index card for Vincenzo Giancola. You should write to NARA to request his file. If you write immediately, there’s a very good chance you’ll receive the file before you leave for Italy.”

Rena acted promptly, and on October 24 she received a digital copy of Vincenzo’s file. The claim revealed that not only had Vincenzo sheltered her father, but also two other Americans—Robert Dunfee and Delvaughn Elliott. All three men were captured on the same day in Tunisia, so perhaps they served in Willman’s company. He might even have known them before they were taken prisoner.

I shared Vincenzo’s claim with Paolo, who immediately began a search for Vincenzo’s descendants.

Three days later he wrote: “With the letter’s information I tried to contact relatives of Vincenzo. I had success. I have found a granddaughter of Sabatino, a brother of Vincenzo. She said she will put me in touch me with the daughter of Donato. Donato is still living.”

What wonderful news—Rena and Molly were now well prepared for their Italian adventure!

In December, after their return from Italy, Rena and I talked on the phone, and she gave me a recap of the experience.

I asked her how she decided to make the journey to Servigliano at this point in time.

“My oldest daughter’s husband has offices in London,” she explained, “and the last three years she’s invited me to come for a visit while they were there. This year she said, ‘We’re going to Tuscany for vacation after our time in London, so you’d be welcome to come and join us for that.’

“I thought, my gosh—Italy is where my dad was a prisoner of war. I should really check and see where Tuscany is in relation to the prison camp. I talked to my brother, got reacquainted with your blog, and did some reading. And then finally I connected with you.

“I got the three-ring binder that holds our dad’s war materials from my little sister, Marci. And that’s when I found the letter from Vincenzo!

“Marci was responsible for gathering [our dad’s war materials] together. My mother had saved these items, and they were found combined with a lot of clutter and junk mail [that collected] during her decline with dementia. I can imagine it was like combing through seaweed to unearth the sunken treasure. Marci and I have had some great conversations during my preparation for travel to Italy.

“And then you introduced me to Paulo.

“I do things pretty spontaneously. Initially, the plan was for me to make the Servigliano journey alone. When my daughter Molly decided to join me she had just two weeks to book the ticket and get her schedule squared away. I was so glad she was able to come with me, as she was the perfect companion.

“When I sent Vincenzo’s letter to you it was only three or four weeks before the trip. Meeting Vincenzo’s family was not something I had contemplated at all before September.

“As a young person I really had little comprehension of who my dad was; I lacked the ability to even ask what life was like for him. I remember in 1979 [our local] newspaper interviewed him for an article. [See “Willman King—A 1979 Article.”] That’s probably where I heard most of my stories about what [the war] was like for him.

“There were nine kids in our home. Home was a busy place. Dad had his first heart attack at the age of 42. I’m guessing atrial fibrillation was part of it, because I remember in my early teen years he would need to be aware of his resting heart rate and sometimes have his heart shocked in order to get it into a good rhythm again. I just kind of lived with that. From my teen years on I felt very aware that he wouldn’t live forever. Near the end he developed congestive heart failure.

“I think cigarettes were probably a big part of it. My dad smoked, I think maybe until the late ’60s. He was a closet smoker—never around us, but then we’d find a pack of cigarettes hidden in the car underneath the dash.

“Also, the VA had determined that sometimes prisoner of war veterans, because of the malnutrition and poor living conditions [they experienced] developed heart problems.

“Regarding the trip, it was hard for me to fully enjoy Florence and the surrounding areas [on the first couple of days]. I told my family, “OK—I’ve got something big and important to do, and it’s really hard for me to just sit here and enjoy this time with you guys.” I felt like my trip was still waiting to happen.

“Molly and I rented a car in Florence, and I’m so happy we [drove the whole way] because it’s more rugged, more rural and beautiful where we were going—vastly different than Tuscany.

“We got to the camp and met up with Paulo there about an hour before the others arrived.

“[During the tour] Paolo Giunta La Spada’s daughter, who had lived in London and spoke fluent English, was a true translator. We spent a really great hour together. The time went so quickly, but I came away with a wealth of information. I told Molly I feel like I just drank from a fire hose—there was just so much to learn! Afterwards we saw the little video that Casa della Memoria made—a reenactment of how the escape happened. There was a diorama of the barracks in the museum; that was helpful because the buildings no longer exist in the courtyard. For me it was kind like continuing to put pieces together.”

You can view the video Rena and Molly watched, Fuga del Campo 59 (Escape from Camp 59), on YouTube. The film is in Italian with English subtitles.

Recognizing that Rena would be too busy and excited to email me details of the trip in real time, I emailed Paolo to ask how things were going.

He sent me a detailed account:

“I left for Servigliano on Thursday morning, arrived around 12. While I was having lunch of a porchetta sandwich and a beer, I wrote to Rena.

“She replied that she was in Servigliano and at 1 pm she would be at Parco della Pace—the site of Camp 59. I headed straight there. After parking in front of the museum I entered the walled perimeter. On the other side were two women. With a wave of my arm, they responded. They were Rena and Molly.

“I approached quickly, and we introduced ourselves. In starting our conversation, I told them of the stories about escaped POWs I had learned from my father and elders from my village, Falciano.

“We reconstructed the journey of Rena’s father, Willman King, from Tunisia to Servigliano—his passing through Sicily and Capua on the way.

“Casa della Memoria staff members Paolo Giunta La Spada, his daughter Carla, and Ian McCarthy arrived at the camp.

“The visit to the museum began, and there Rena and Molly saw and understood what life was like in the camp, what the escape was like and how difficult it was to move around in a country, Italy, in midst of civil conflict after September 8th. After our time in the exhibition we visited the camp, saw where the hole was dug through the wall for the escape, the guard barracks that remain, and—in a sort of space-time suspension—gazed at three large oaks inside the camp that were so old that surely Willman also saw them.

“With much emotion and reflections, we left the camp and headed by car to Ascoli Piceno, winding along hills that Willman likely also crossed.”

Rena told me, “That night Molly and I stayed in a bed and breakfast just outside of Ascoli. In the morning, using my phone to translate, I explained to the owners we were on our way to meet the family that cared for my dad as an escaped prisoner of war. That opened up a whole conversation with them. They told us about how just across the valley on a hilltop there was a castle that the Germans destroyed because the people had harbored an English soldier there. The whole countryside knew about this because the son of the family at the bed and breakfast had done a blog post about that castle.” (Read the article on The Italian Insider.)

Paolo emailed me again that day:

“I was with Rena and Molly until one hour ago. It has been two wonderful days. First yesterday at the camp, and today with the Giancola family—very emotional. Two wonderful persons meeting like siblings separated after birth. Listening to Donato had been really exciting. He is such a kind person. And Rena, a strong woman, getting emotional when seeing for the first time the land where her father once hid.”

At the Giancola home Rena and Molly met Donato, Donato’s daughter Vincenzina, Donato’s brother Mario, and Mario’s wife Bruna.

During the visit Rena and Molly also met Sergio, son of Donato’s uncle Sabatino. It was Sergio’s daughter Manuela who responded to Paolo’s Facebook message when he was attempting to contact Giancola descendants; it was thanks to Manuela that this reunion had become a reality.

Rena described the visit:

“I had brought a photo of my dad in his uniform as a 20-year-old, my parents’ wedding picture, and a family picture taken in 1979—just a year before my dad died—that had all nine of us kids and mom and dad. I also brought a photo that was taken ten years later, which includes multiple grandchildren. It was really moving to share the photos because it was like saying, “You guys cared for my dad, and none of this would have happened without your care and love and protection.

“They had pictures also—of Vincenzo and his wife, and Mario as a young child, and I saw pictures of Donato as a young man and then featured in a newspaper article when he was working in a Ford plant in Belgium. In talking with Donato and Vincenzina, I felt like I was appreciating another piece of my own family—on the other side of the equation—realizing they were in jeopardy for harboring the soldiers. They talked about how my dad and the other soldiers were sent packing into the woods [for safety], and then just a couple days later Vincenzo and his family had to flee also, and I’m thinking, ‘My gosh, this is so much deeper than you can even imagine. They had a baby that was just a couple of days old when they fled.’”

Vincenzo’s wife was Carolina Pavone, The couple had 13 children, but four died as infants or in childhood.

“After breakfast we left for the farm where Vincenzo’s family had lived. The frame of the house is still there. It’s a rock house and much of it is now dilapidated. That family was living in that one-room house; I think there were seven living in the one room. When I was born my family did not have running water either, so I could understand, or maybe just visualize, what [that way of life] was like for this family.”

“The bar-restaurant where we ate that day was a building that existed during the war. The Germans commandeered the place as their headquarters. I can’t imagine what that would have been like. Whatever family was living there had to move out. We had a four- or five-course meal. That was one of the things about Italy that impressed me, they do have multiple courses and the meal can go on for a long time.”

“I still wanted to go exploring, so on Saturday Molly and I [drove back to the area and] hiked into the valley. It took us all morning. I think it was three miles down and three miles back up, and we walked around down in the valley. It was a good place for us to talk about what we had just experienced.

It felt good to burn some energy. In returning to Ascoli with Paolo the day before we had taken the toll road, and so on the way back to the area we did not take the toll road. It was such a beautiful drive—it was cloudy and cool and during the whole drive we were in the countryside.”

“A picture was taken of Donato and me together,” Rena said, ”and Vincenzina later texted me that someone mentioned Donato and I have much the same facial features. I mean, that we look alike, as if we are siblings—of different mothers, you know—and that was a cool thought.

“Mario wasn’t alive during the war. When we said goodbye he gave me a bear hug and he was quite emotional. This was a very moving experience for him. He sent an e-mail through Paolo later, where he said, ‘I asked my mother to tell me this story many times and she had talked about the soldiers being with us and it was a fearful time.’ But there was also a lot of joy and celebration for them.

“I was thinking Mario being the youngest child, he probably feels like he missed out on stuff with his dad. That might have had something to do with the emotional impact of the visit for him—like rediscovering this experience that his dad and my dad had together. It was a hard life for his family. Longevity now is different than it was in the ’30s after the Depression. Life was hard and it took a toll. I felt sorrow for their family for losing Vincenzo, and for Mario to lose his dad at the age of three. Gosh, you know times were rough when you realize so many children didn’t survive infancy.”

“As our traveling buddy, Paola was fun and genuine—I mean he cared for us. Molly and I would have been really lost if we hadn’t had him as a guide. As a nurse I care for patients who speak other languages, and I have to find ways to communicate. But I know it’s not easy. It’s hard work to do that, so we greatly appreciated his help.”

Vincenzina and Rena have remained in contact via text since Rena and Molly returned to Minnesota.

“When we got home, a week or two passed by and then we had snow.” Rena said. “I sent a message to Vincenzina to ask, “Is it snowing there?”

“It seems like the climate in Roccafinadamo would be much the same as here in Minnesota, so I figured maybe if it’s cold here, it’s cold there. I know there was snow on January 1st when my dad was staying in the stable so, yeah, when you get into the higher elevations in Italy they get a lot of snow up in the mountains.

In early January, Vincenzina texted to Rena:

“I too have learned many things that I didn’t know before you came to Italy … those little houses where my father took us … he never wanted to take us. I didn’t know [of their] existence, he always says that he suffered so much and that’s why he never took me there … it was a reliving of a not so beautiful period unfortunately. But the beauty of this story is that God made us meet unexpectedly, who would have ever said it [was possible]. I’m not saying it’s a miracle but almost … My father still gets emotional today when he thinks back to your meeting. For us now you are part of our family and you are always welcome in our home. We send you a big hug and kisses.”

Rena is already talking about a return to Roccafinadamo, but this time she plans to bring her two sisters. Having heard Rena’s stories of the happy reunion, Marci and Michelle are eager to meet their new Italian family!

Hi Denny, Congratulations for this excellent post, story and documentation! Warm Regards, Luigi

Luigi Donfrancesco luigi.donfrancesco@gmail.com