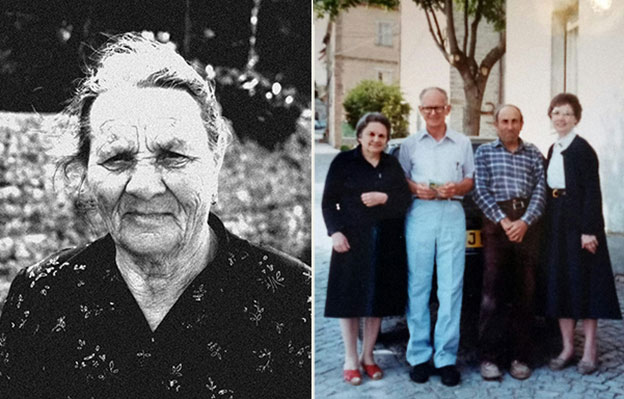

In my 2020 post A Haven in Smerillo, I shared a story about the sheltering of two escaped POWs by a remarkable woman, Letizia Galiè in Del Gobbo, a widow with six children.

The story of Letizia Del Gobbo’s heroism came to me from her grandson Marco Ercoli. When Marco contacted me, he recalled that the family simply referred to the two escapees as “Michele” and “Beo.”

Marco recalled that “Beo” had years ago returned to Smerillo with his wife, Nadine. The 1990 homecoming was deeply emotional for both the American couple and everyone in Smerillo—both family and older neighbors. In relaying the story, Marco described the event best as he could from memory—taking a degree of creative liberty to enliven it with recreated conversations and detail.

The only evidence of the visit was a photograph of the American couple with Marco’s uncle Antonio and Antonio’s wife Viola, with a notation on the back: “Nadine and Bill.” That made it clear that the man they called “Beo” was Bill, or William.

“Michele” in English would be Michael, and Marco’s uncle Antonio, who was a teenager when his mother sheltered the POWs, confirmed that “Michele” was American serviceman Michael Rotunno.

Since then, in spite of delving into archives, no further information about Bill and Michael came to light until last March, when I discovered that after the war Letizia had submitted a claim to the Allied Screening Commission requesting compensation for sheltering POWs. From the U.S. National Archives (NARA) I ordered a digital copy of Letizia’s helper claim.

The claim turned out to be a goldmine of information.

Letizia’s Helper Claim

Not only had Letizia Del Gobbo sheltered Michael Rotunno and Bill, who was identified in the claim as William Fleischauer; she had sheltered two other POWs—and, according to Michael Rotunno, she fed several other POWs who were in the area.

The four escaped POWs—all from PG 59—were named in a chit written by Micheal. The chit specifies the POWs arrived at Letizia’s home on 17 September 1943—just three days after the camp breakout. Sergeant Irving L. Rosen and Staff Sergeant Ivan J. Robinson stayed with Letizia for only a few weeks.

Sgt. Michael J. Rotunno

12018732 U.S. Army

U.S.A.

S/Sgt. William Fleischauer Jr.

12013944 U.S. Army

U.S.A.

Sgt. Irving L. Rosen

6250 N. Washtenaw Ave

Chicago, Illinois

U.S.A.

S/Sgt. Ivan J. Robinson

504 Exter Ave

Middlesboro

Kentucky

U.S.A.

It was not unusual for a POW who was sheltered by an Italian family to leave behind a chit—a note acknowledging the Italian’s kindness in caring for the escapee. Chits typically have a soldier’s name, rank/serial number, home address, and sometimes a reference to the length of time spent and types of help provided by the family.

Michael went beyond that. Remarkably, he left four chits with Letizia, dated from 17 November 1943 to 21 June 1944. His heartfelt appeal, addressed to Allied authorities, would in time ensure his protector received compensation.

“She took care of us when we were ill … & paid all medical bills for me, “Michael wrote. “I and 14 other soldiers have been eating at this house. … It cost her 1,300 lire for a new pair of shoes for me, she bought a shirt at [a] cost of 700 lire.”

In his last chit, Michael noting he had been staying with Letizia for nine months. He made this final appeal: “ … if there’s anything you can do, kindly aid her. She is a widow with 6 children, income for her is probably nothing at all. Sir even if the things you give them cost a lot take it out of my pay. She’s treated every prisoner with all her heart. … Kindly & please see that she’s well taken care of.”

Compensation

Letizia’s helper claim includes separate pages for each escapee:

Michael James Rotunno

Lodging and food, 16 September 1943–30 June 1944

Money supplied—300 lire

Help with a hiding place during the German roundup

William Fleischauer Jr.

Lodging and food, 16 September 1943—20 March 1944

Clothing (socks, underpants), other necessities, washing, cigarettes, and medicines

Money supplied—500 lire

Ivan J. Robinson

Lodging and food, 16 September—16 October 1943

Irving L. Rosen

Lodging and food, 16 September—16 October 1943

Spent 100 lire looking after him while ill

Amount authorized and paid to Letizia Del Gobbo

Food and lodging supplied—38,740 lire

Clothing supplied (shoes 1,000 lire / shirts and vests 1,500 lire)—2,500 lire

Money supplied—900 lire

General unspecified assistance—860 lire

_____

Total, 43,000 lire

The claim specifies Letizia cared for one POW for nine months [Michael Rotunno], one POW for 6 months [William Fleischauer], and two POWs for one month each [Ivan Robinson and Irving Rosen].

The Infantryman

Sergeant Michael Rotunno was a member of the U.S. First Infantry Division, known as “The Big Red One.”

Michael was captured on Christmas Day 1942, apparently at Longstop Hill, a strategic position near Medjez el Bab, when the Germans retook the hill from the Allied forces. On being transferred from North Africa, Michael was first interned in Sicilian camp PG 98, a camp through which many POWs passed on their way to the Italian mainland. Then Michael was sent to PG 50. Based in the Italian cavalry’s Caserna Genova Cavalleria Macao barracks in Rome, PG 50 was a special interrogation camp through which prisoners might pass for questioning before being sent to a “standard” POW camp.

Like Michael, American infantryman Arthur T. Sayler was sent from PG 98 to PG 50 before final internment in PG 59.

Reading about Arthur’s interrogation helps us to understand what Michael likely experienced in PG 50:

Arthur and about 12 other men were taken to central Rome for special interrogation. The treatment in Rome was very good. Each man received a Red Cross parcel of food twice a week. The American’s uniforms were taken from them, and they were issued new British uniforms.

The men found that the sleeping quarters were more than adequate. However, they suspected, given their good treatment, that the place was bugged with microphones, so they were careful what they said.

During the two weeks stay, each man was taken into a room for interrogation.

When Arthur gave only his name, rank, and serial number, the interrogating officer who was sitting opposite him became irritated, pulled a pistol from his holster, and placed it on the table as a threat. When Arthur continued to refuse his questions, the officer said, “Now let me tell you some things,” and he recounted in detail almost every move Arthur’s unit had made since leaving the U.S. He knew places, dates, and times.

He spoke English very well, and told Arthur he had a degree from Yale University.

Michael was in PG 50 for a little over three weeks and then transferred to PG 59. His repatriation record indicates his last camp was PG 59 Servigliano (indicating he was not recaptured after his escaping from PG 59). He was still living with Letitia at the end of June 1944 when the Allied forces arrived in the area.

The Three Airmen

Three of the escapees—Sergeant Irvin L. Rosen and Staff Sergeants William Fleischauer Jr. and Ivan J. Robinson—were airmen in the U.S. Army Air Force.

Following the invasion of Sicily (Operation Husky) on 10 July 1943 and in anticipation of the Allied landings near the port of Salerno (Operation Avalanche) on 9 September, Allied bombers aggressively attacked Italian infrastructure, such as airfields, harbors, and railways, in the coastal area around Naples and Salerno. The three airmen had been an active in this bombing operation.

On 17 July 1943 their B-26 bomber was downed near Pontcagnano Faiano, Salerno.

The three were sent to CC Poggio Mirteto for interrogation and afterward transferred to PG 59.

In an interview with James Diehl for Morning Star (July 31–August 6, 2008) Bill Fleischauer explained that he initially was told he didn’t meet fitness requirements for fighter plane duty. Instead he was assigned to work as a flight mechanic.

His situation changed unexpectedly:

All of a sudden, after being told for months that he wasn’t in good enough shape to be trusted on a fighter plane, Fleischauer got the news that he would, indeed, be needed.

“The crews all got shot up and they were missing a tail gunner. So, I got a job,” remembers Fleischauer, who was assigned to the 438th squadron of the 319th bomb group. “I was really happy about that, but I had very little training. They were just desperate for people.”

It didn’t take long for Fleischauer to get in on the action—on his very first mission, in fact.

“We were going to one of the islands [near] Italy to bomb bridges and warehouses,” he recalls. “We flew six planes and we were in the back end. One of the German fighters came up on our tail and I shot at him. He went down but I don’t know if I was the one who shot him down or not.”

There was also fire coming from below, which happened on every mission because Fleischauer’s B-26 flew at just 5,000 feet off the ground, often in the daylight.

Those two facts together created many harrowing situations.

“One time. I had a flak hole in between my legs,” he remembers. “If I had been squatted down, I wouldn’t be here today. But, I was standing up and it went right between my legs. I didn’t even know about it until after it happened.”

Everything Fleischauer encountered in the skies led up to his 11th mission—the one he wouldn’t return from.

“We were bombing the waterfront and the docks at Naples. We had already dropped our bombs and were about 25 miles east of Naples when flak from the ground blew our motor out.” he says. “The pilot said to bail out, but I had never received any instructions on the parachute… They just told me to pull the ripcord.”

He did as he was told and began floating to the Italian countryside below, understandably feeling a bit nervous. So, he thought he’ d calm his nerves with a little tobacco.

“I tried to light my cigarette coming down, but it wouldn’t work,” Fleischauer says with a grin. “It was a nice ride coming down but I landed in a field and a rock hit me right in the tailbone.”

Later in the same interview, Bill described his escape from PG 59 and his encounter with Letizia Del Gobbo:

“We went up the hills; there were three of us. When we got to the top of this hill, there was a woman out [collecting] branches. They couldn’t cut the trees down, but they could get the branches that had fallen down for firewood.”

With four young children—two boys and two girls—the woman saw the men, recognized them as Americans and invited them to stay on her property.

She knew there would be seriously consequences if she was caught, but she made the offer anyway.

“She basically just said to come home with her and she put us up in her chicken house,” remembers Fleischauer, who said one of his colleagues left after just a couple of days.

“It was warm then and when it got colder she took us into the house. But if the Fascists came, we had to take off.

“One night, we took off and ran across a churchyard which was just across the street from where we were living,” he says. We jumped over a wall and there were a couple of trees there, and a straight fall down about 300 feet. Fortunately, the trees held us.”

They returned to the chicken house that same night, continuing the routine many times for the more than 10 months they remained hidden in the small Italian town of Smerillo.

“We’d have to go out several times during the winter when the Fascists were looking for us, but she knew when they were coming. They couldn’t sneak up on us because there was only one road up to this town where we were hiding.”

Finally, after close to a year in hiding, the Americans and Russians advanced far enough into Italy where Fleischauer and his partner could return to Allied lines.

On his return to the States, Bill Fleischauer worked for the U.S. Postal Service; he then became a minister and founded Hickory Ridge Community Church in Greenwood, Delaware.

In 1990, he was suddenly struck by a need to return to Italy to once again see and formally thank Letizia’s family.

The Morning Star interview touches on Bill’s decision to visit Smerillo with Nadine:

“I was preaching about the 10 lepers and how one of them went back. The Lord just convinced me that I needed to go back to Italy,” he says. “We rented a car and had to stop at a bookstore to buy a book and find out where the place was.

“But we finally found it and drove up in the churchyard. The priest’s old housekeeper recognized me by my smile, took us in and gave us some cookies.”

While the old widow had died just a year earlier, Fleischauer was united with all four of her children and had the chance to give each of them a heartfelt thank you for everything they did for him during wartime.

Bill said in the article that Letizia had four children. One of Michael’s early chits references five children, but in a later chit he references six children. Marco Ercoli clarified the number for me. In actuality, Letizia had six children:

“The family Del Gobbo in 1943 was made up of my grandmother Letizia, widowed in 1936, and three sons—Antonio, Giacomo, and Giuseppe—and three daughters—Maria, Chiarina, and Palma (my mother).”

William Fleischhauer Jr.

In addition to his work for the U.S. Postal Service and the founding of his own church, Bill Fleischaurer owned and operated both a funeral home and a lumber company. He and Nadine were married for nearly 74 years; they had three children. At the time of Bill’s death he and Nadine had many grandchildren, great-grandchildren, and great great-grandchildren.

Fleischauer, William

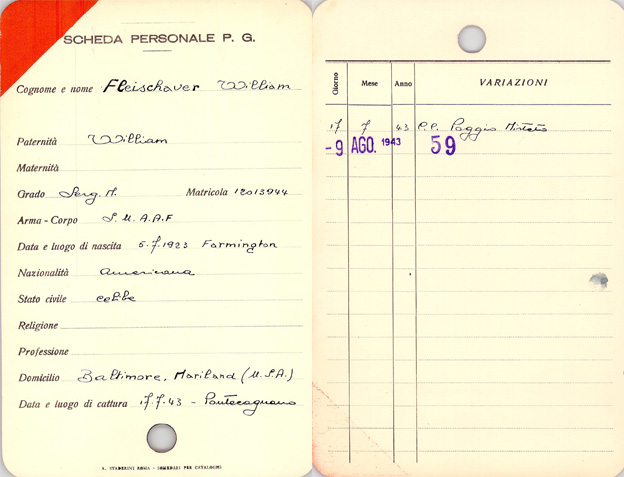

SCHEDA PERSONALE P. G.

[PERSONAL CARD of PRIGIONIERO DI GUERRA, prisoner of war]

Cognome e nome [Surname and name]: Fleischauer, William

Paternità [Father]: William

Maternità [Mother]: –

Grado [Rank]: Serg. M. [staff sergeant—the equivalent of sergente maggiore in the Italian army]

Matricola [Service number]: 12013944

Arma-Corpo [Service unit]: S.U.A.A.F [United States Army Air Forces]

Data e luogo di nascita [Date and place of birth]: 5 February 1943 Farmington

Nazionalità [Nationality]: Americana

Stato civile [Marital status]: celibe [single]

Professione [Occupation]: –

Domicilio [Residence]: [1601 Linden Avenue] Baltimore, Maryland (U.S.A.)

Data e luogo di cattura [Date and place of capture]: 17 July 1943 Pontcagnano [Pontcagnano Faiano, Salerno]

Giorno/Mese/Anno/Variazione

[Day/Month/Year/Change]

17 July 1943 – CC Poggio Mirteto [an interrogation camp]

9 August 1943 – 59

Bill’s enlistment records indicate he was born in Delaware in 1923, had four years of high school, and was a semiskilled automobile mechanic or repairman. He enlisted on 14 July 1941 in Dover, Delaware.

William’s repatriation record shows he was repatriated from PG 59 Servigliano; in other words, he was not recaptured after his escape from PG 59.

Ivan J. Robinson

Ivan Robinson died at the age of 36. He is buried in Highland Memory Gardens. Chapmanville, West Virginia.

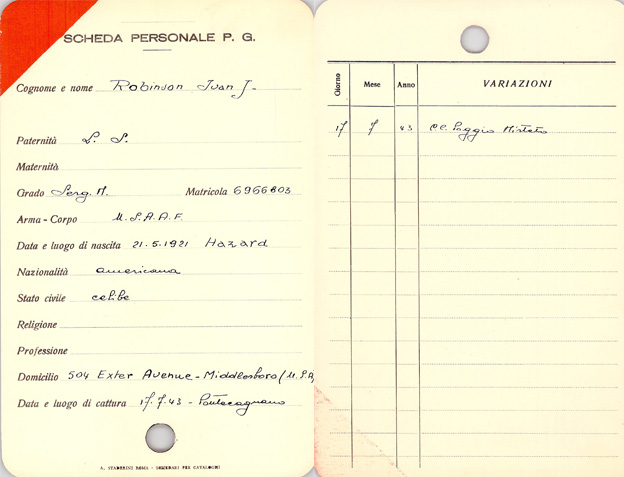

Robinson, Ivan J.

SCHEDA PERSONALE P. G.

[PERSONAL CARD of PRIGIONIERO DI GUERRA, prisoner of war]

Cognome e nome [Surname and name]: Robinson, Ivan J.

Paternità [Father]: L. S.

Maternità [Mother]:

Grado [Rank]: Serg. M. [staff sergeant—the equivalent of sergente maggiore in the Italian army]

Matricola [Service number]: 6966803

Arma-Corpo [Service unit]: U.S.A.A.F. [United States Army Air Forces]

Data e luogo di nascita [Date and place of birth]: 21 May 1921 Hazard [likely Hazard, Kentucky]

Nazionalità [Nationality]: Americana

Stato civile [Marital status]: celebe [single]

Religione [Religion]: –

Professione [Occupation]: –

Domicilio [Residence]: 504 Exter Avenue – Middlesboro [Kentucky] (U.S.A)

Data e luogo di cattura [Date and place of capture]: 17 July 1943 Pontcagnano [Pontcagnano Faiano, Salerno]

Giorno/Mese/Anno/Variazione

[Day/Month/Year/Change]

17 July 1943 – CC Poggio Mirteto [an interrogation camp]

There is no enlistment record for Ivan Robinson in the U.S. National Archives database.

Ivan Robinson’s repatriation record shows he was repatriated from PG 59 Servigliano; in other words, he was not recaptured after his escape from PG 59.

Irvin L. Rosen

According to an obituary in Jewish United Fund (JUF) Magazine, Irving married Belle Rabinowitz. The couple had three children and, at the time of Irving’s death on 20 November 2003 at the age of 88, they had nine grandchildren. He was laid to rest in Westlawn Cemetery, a Jewish cemetery located in Norridge, Illinois, a suburb of Chicago.

Irving’s repatriation record indicates he was recaptured after being on the run in Italy and after leaving Letizia’s home; he subsequently interned in Stalag Luft 3 Sagan-Silesia Bavaria (moved to Nuremberg-Langwasser).

Needless to say, Jewish POWs faced unique danger in German camps.

Frederick Solberg, who was recaptured by the Germans following his PG 59 escape, had this to say regarding his internment in Stalag 17B:

I’m Jewish. So that was one of my worries. I’ve heard stories about the prison camps where they cull out people that looked Jewish—or were Jewish—either way … they took them away and we never saw him again. … If you kept your nose clean and everything, then you were OK—unless you were Jewish.

And POW Felice “Phil” Vacca remarked, “The captain of our company was Jewish. After being captured, he managed to lose his dog tags. Otherwise, the Germans would have treated him differently.”

Rosen, Irving L.

SCHEDA PERSONALE P. G.

[PERSONAL CARD of PRIGIONIERO DI GUERRA, prisoner of war]

Cognome e nome [Surname and name]: Rosen, Irvin[g] L.

Paternità [Father]: Louis

Maternità [Mother]: –

Grado [Rank]: Serg. M. [staff sergeant—the equivalent of sergente maggiore in the Italian army]

Matricola [Service number]: 16004952

Arma-Corpo [Service unit]: U.S.A.A.F. [United States Army Air Forces]

Data e luogo di nascita [Date and place of birth]: 22 December 1914 – Chicago

Nazionalità [Nationality]: Americana

Stato civile [Marital status]: celibre [single]

Religione [Religion]: –

Professione [Occupation]: –

Domicilio [Residence]: [6250 N. Washtenaw Avenue] Chicago – Illinois

Data e luogo di cattura [Date and place of capture]: 17 July 1943 Pontcagnano [Pontcagnano Faiano, Salerno]

Giorno/Mese/Anno/Variazione

[Day/Month/Year/Change]

17 July 1943 – C.C. Poggio Mirteto [an interrogation camp]

The enlistment record for Irving Rosen indicates he had three years of high school education and at the time of his enlistment had civilian experience as a photographer. He enlisted on 23 June 1941 in Chicago, Illinois.

Michael James Rotunno

Michael enlisted in the U.S. Army on 8 October 1940 in New York, New York. At time of enlistment he had a grammar school education.

Michael died at age 53. He and his wife Josephine Rotunno (19 March 1917–13 November 2007) are buried together in Long Island National Cemetery, East Farmingdale, New York.

Rotunno, Michael James

SCHEDA PERSONALE P. G.

[PERSONAL CARD of PRIGIONIERO DI GUERRA, prisoner of war]

Cognome e nome [Surname and name]: Rotunno, Michael James

Paternità [Father]: Joseph

Maternità [Mother]: Elizabeth

Grado [Rank]: Sgt. [Sergeant]

Matricola [Service number]: 12018732

Arma-Corpo [Service unit]: Infantry

Data e luogo di nascita [Date and place of birth]: 18 May 1919, New York

Nazionalità [Nationality]: American

Stato civile [Marital status]: Single

Religione [Religion]: Catholic

Professione [Occupation]: Labourer

Domicilio [Residence]: 145 East 29th Street, Brooklyn, New York

Data e luogo di cattura [Date and place of capture]: 25 December 1942 Tunisia

Giorno/Mese/Anno/Variazione

[Day/Month/Year/Change]

28 December 1942 Guinto a questo campo proveniente dalla Tunisia [coming to this camp from Tunisia] C.C. 98

13 January 1943 C. 50

5 February 1943 C.C. 59

Michael Rotunno’s Chits

Here is the text of the four chits Michael left with Letizia Del Gobbo:

November 17, 1943

To whom it may concern:

I & a companion have been staying at Signore Litizia [Letizia] Del Gobbo[’s] home for 2 months. They fed us 3 meals a day. We arrived at her home September 17, 1943. She took care of us when we were ill. She has paid 140 Liras for medical care. Please see that she is well taken care of I thank you.

Sgt. Michael J. Rotunno

12018732 U.S. Army

U.S.A.S/Sgt William Fleischauer Jr.

12013944 U.S. Army

U.S.A.[At the bottom of the chit are the words “3 weeks” and two arrows point to Sgt Rosen and Staff Sgt. Robinson.]

Sgt. Irving L. Rosen

6250 N. Washtenaw Ave

Chicago, Illinois

U.S.A.S/Sgt Ivan J. Robinson

504 Exter Ave

Middlesboro

Kentucky

U.S.A.

Dec. 13, 1943

To whom it may concern,Dear Sir:

Have been staying at Mrs. Litizia Del Gobbo’s home for 3 months. She’s treated us fine & paid all medical bills for me. Perhaps you can help her. She is a widow with 5 children. I thank you.

Sgt. Michael J. Rotunno

12018732 U.S. Army

United States of America

Sept 17–Dec 14, 1943

June 17, 1944

Dear Sir

Kindly treat this family with respect. They’ve treated all prisoners of war with all their heart. I and 14 other soldiers have been eating at this house. Please see that their [they’re] taken care of. Even if it comes out of my pay. They’ve taken care of me for nine months. The whole town has treated prisoners of war fine. I thank you.

Sgt. Micky Rotunno

Serial No. 12018732

United States Army

18th Infantry 1st DivisionSeptember 17, 1943

June 17, 1944[On this chit Michael has drawn the emblem of his unit the 1st Division.]

June 21, 1944

Dear Sir,

I, Sgt. Michael J. Rotunno Serial No. 12018732 have been staying at this home of Signore Litizia Del Gobbo, Smerillo, A. P. [Ascoli Piceno] for nine months, if theres anything you can do, kindly aid her. She is a widow with 6 children, income for her is probably nothing at all. Sir even if the things you give them cost a lot take it out of my pay. She’s treated every prisoner with all her heart. For 3 months she’s [kept] I & 5 other Sgt[s] at her home. Kindly & please see that she’s well taken care of. It cost her 1,300 lires for a new pair of shoes for me, she bought a shirt at [a] cost of 700 lires Thank you Sir.

Sincerely yours

Sgt. Michael J. Rotunno

What a blessing to find this story. I recall my grandfather (Bill) telling us about how God used this family and it’s so amazing to find out more details years later.

Sincerely- Bill’s granddaughter