Pte. David Garcia, 1/4 Battalion, Essex Regiment, was deployed to North Africa during WWII, captured near Mersa Matruh in June 1942, and interned in PG 102 L’Aquila, Italy. After the September 1943 Italian Armistice, David and the other prisoners left the camp.

David and another escaped prisoner, Patrick Callan, made their way to San Giacomo, where they were protected by the Umberto Capannolo and his family. We don’t know if Patrick was interned in PG 102, or whether David met him while on the run.

“It was not safe for David and Patrick to stay with Umberto’s family, so his sons established a bivouac for them in a cave at the edge of some woods,” said Roger Bickmore (husband of David’s granddaughter Miranda). “They then considered it to be too close to the road and found another cave deeper in the forest.”

One year ago I wrote about a reunion of David’s family and Capannolo descendants. (See “A Joyous Reunion—the David Garcia and Umberto Capannolo Families Meet.”)

During the past year, Roger has been hard at work tracking Patrick.

Here are the recent developments in Roger’s own words:

The Other Man in the Cave: My Search for Patrick Callan

“Last February I shared the story my of meeting the Capannolo family in L’Aquila the previous summer with my mother-in-law, Linda. They gave shelter to her father, David Garcia, for several months after the armistice in 1943. Their identity was only revealed when Linda discovered an address on a letter from the Red Cross in David’s old tin box decades later. The opportunity to finally thank these wonderful people proved to be as memorable as we had hoped.

“My report of this joyous occasion, however, ended on a cliffhanger of sorts. We had not expected to be told that David had a companion hiding with him in the hill caves behind their farm: apparently a soldier from South Africa called Patrick. On hearing this surprising news, I decided to find out who he was and whether he had surviving relatives. With so little to go on I was unsure where to start. Thankfully, Anne Copley of the Monte San Martino Trust pointed me in the direction of the American National Archives (NARA).

“NARA holds 1.5 million documents produced by the Allied Screening Commission (ASC), a body tasked after the war to reward Italians who aided escaped POWs. On a digitised rolodex of those who had presented claims for compensation were several with the family name Capannolo. I narrowed my choice down to a handful of files, two of which were of special interest. The first was for Umberto Capannolo, whose descendants we had met in Italy. The second was for his brother Beniamino, who the family had said looked after Patrick for a while when David fell sick. After requesting the documents and paying the fee, it took a few months before I was eventually emailed PDF copies. The wait was worth it.

“In support of his claim, Umberto had submitted a letter of thanks that David had written to the family after his return to UK. Also, prior to leaving the farm, David had also given Umberto a handwritten chit. These short testimonies were quite commonly left behind by POWs, so that their helpers might be reimbursed later from the army for the food and shelter they had provided.”

Here is David’s letter:

Mr. D. Garcia

168, Imperial Ave

Stoke Newington

London, N. 16

England20th July 1945

Dear Umberto & Family,

I was very pleased to have received your message & am delighted to hear that you and everyone at home are all well.

I am always thinking of you & your family & also everyone who I know in S. Giacomo who has been so kind to me during my escape & so made it possible for me to return to England & also to my wife & son. I hope that one-day we will be able to meet again under better circumstances.

Do you remember the cave I use[d] to hide in, which was my home for ten months, well I would like you to take a photograph of it & send it to me. I was very glad to hear that your country has been Liberated by our forces & that you are now free from the Germans & their terror acts for good.

I hope that the Allied Military Government has compensated you for all the good work you have done for me, & also other prisoners of war.

Well Umberto, this is about all I can write at present.

Good wishes & greetings from my wife son & myself.

Best of Love to all

David

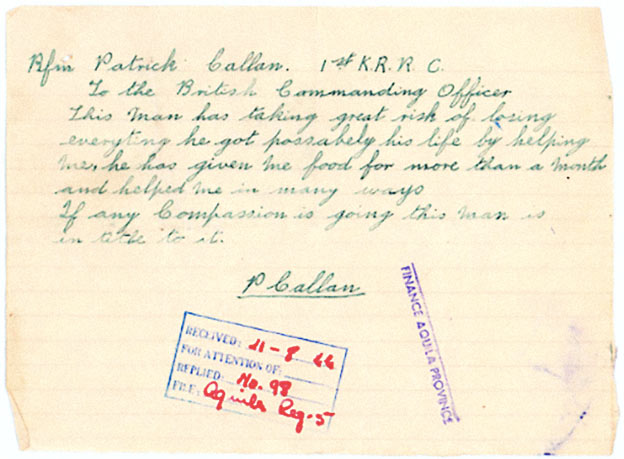

“Umberto’s brother, Beniamino also possessed a chit, like the one David had given, but Beniamino’s was written by Patrick.”

Ffm Patrick Callan. 1st K.R.R.C

To the British Commanding Officer

This man has [taken] great risk of losing everything he [has] got [including] possibly his life by helping me, he has given me food for more than a month and helped me in many ways

If any Compassion is going this man is [entitled] to it.

P. Callan

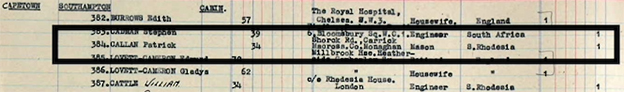

“Having this new information, I was able to confirm Patrick’s identity in the International Red Cross POW register. I also recovered three military records from the Ancestry website that gave me the dates of Patrick’s capture in North Africa, imprisonment, and eventual return to the army. This was a promising start.

“One aspect that immediately puzzled me, however, was his regiment, which was London-based. For a time, I questioned whether there was any sort of South African connection at all. A member of the WW2Talk online forum was very helpful, explaining to me that the Kings Royal Rifle Corps had a connection to Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) so it was plausible that he was recruited from there, rather than neighbouring South Africa.

“I studied the shipping manifests and found three interesting entries. A Patrick Callan sailed out from Southampton to Cape Town in 1937. The same man then journeyed to UK and back in 1948. He travelled alone and his age on the register suggested a birth year of around 1914, which would make him the correct age to be in Italy during the war. Better still, the man’s departure point for his 1948 trip was recorded as Rhodesia. Interestingly, his destination was stated as Carrickmacross, a small town in Ireland.”

“I suspected that this Patrick was originally from Ireland, and he may have emigrated to Rhodesia in 1937 at the age of around 23, and then returned home for a visit in 1948. I discovered plenty of Callans in Carrickmacross on the Ancestry website. After some painstaking hours at the computer, I concentrated on two Patrick Callans born in the town in 1914. I reached out online to their descendants, but no one recognised the story I was telling about the escaped POW who left for Rhodesia. The trail started to go cold.

“Then someone on Ancestry suggested I ask the Carrickmacross Genealogy Facebook Group for help. I posted my story, and one of its members, Desmond, replied. He thought that his grandfather was Patrick’s brother. It was an agonising wait whilst Des spoke to his mother and older relatives. Unfortunately, they knew little of what had happened to Patrick after he left Ireland. However, miraculously Des somehow found the Facebook profile of a young man called Matthew in the UK who he believed to be Patrick’s grandson.

“It was immediately obvious Matthew was not a regular on the platform. My friend-request to him unsurprisingly went unanswered; Des did not have any other way of interaction. Matthew’s handful of posts were old, but the sparse content did suggest a connection with Zimbabwe. I was sure I was on the right track, but it was deeply frustrating not being able to make contact.

“After a few days of ruminating, I took another look at Matthew’s posts. There was one guy who was a keen Facebook user who had ‘liked’ them. On his timeline, I discovered a recently photograph of him with Matthew. My message for assistance to this buddy worked, because sure enough the following day I got a phone call.

“Thankfully Matthew did not mind me cyber-stalking him. He was excited to hear about my investigation, which by this point even to my own ears sounded on the intense side. He told me that his grandfather was indeed Patrick Callan, Patrick had served in the war, and Matthew was pretty sure he had been imprisoned in Italy. For more information he suggested that I reach out to his mother Mary–Patrick’s daughter—who lives in Zimbabwe.”

“Mary was immediately captivated by my explanation of her father’s wartime experiences and had lots of questions. Just as David never spoke to his daughter Linda about what happened during the war, Mary also had no idea about what Patrick endured. A few years earlier, a house fire had destroyed a lot of her father’s possessions but happily she still had some photographs of her dad. To finally see this man in the flesh was incredible.

“She told me that in the years after the war and before he met her mother, Patrick lived a nomadic life. He returned briefly to Ireland, spent time with his brother in the USA, and then got a job in Australia. He was a builder by trade, eventually coming back to Africa to work on the construction of the railways. In his forties he finally settled down in Zimbabwe, married, and lived out a quiet existence until he was beset by a series of health problems.

“Patrick died in 1983, aged 69, a couple of years before David.

“The two men who hid together for months in a cave on an Apennine mountain went on to lead quite different lives. Yet comparing the accounts of their daughters, Linda and Mary, it is apparent that both David and Patrick were each deeply affected by the trauma of their time evading capture by the Nazis in Italy, as well as the earlier deprivations of camp life and battle scars left from North Africa. Like so many survivors, they withdrew into themselves, revealing virtually nothing of what they went through. With no available interventions, they sometimes struggled to cope.

“The pair were an odd couple—David, a young Cockney Jew who made deliveries in London’s garment district, and Patrick, a well-travelled Irish stone mason born into rural poverty. Whether they formed a bond in their prison camp and there decided to chance it on the run together when the opportunity presented itself, or whether they were just strangers thrown together, their paths literally crossing in the Italian hills, is unknown.

“Perhaps Patrick enjoyed a reunion with David, sharing a pint in an East End pub when he transited through London in 1948, or maybe they simply shook hands in L’Aquila once it was liberated by the Allies in 1944 and went their separate ways. We shall never know.

“My research is almost complete, but I end on perhaps another cliff-hanger.

Earlier I said that I requested several files from the NARA. In addition to the two claims made by Umberto and Beniamino, I discovered a third one, presented by Giovanni, another member of the Capannolo clan.

“Amazingly, Giovanni helped a further six POWs: Drivers Lane and Smith of the Royal Engineers, Private Gaylard of the Dorsetshire Regiment, Gunner Simmonds of the Royal Artillery, Sergeant Major Hope of the Royal Corps of Signals, and Umberto Cerfontaine—a Belgian who served in the French Foreign Legion.

If there is anyone who is interested in these men, please let me know and I would be happy to share my papers and help to track down their descendants. As many of those also fascinated by this extraordinary chapter in Italian history have warned me, the research is quite addictive!”

Anyone wishing to contact Roger Bickmore can respond to this post with a comment or contact Dennis Hill, hilld@iu.edu.