I recently purchased through Amazon a book I have heard about for years, and that I have long wanted to own.

Keith Argraves, Paratrooper by George W. Chambers (published in 1946 by the Southern Publishing Association of Nashville, Tennessee) was among the first Allied POW narratives to be written and published after the war.

The memoir is Keith’s experience as told through George W. Chambers, an Arizona businessman, civic leader, and amateur historian.

The edition I purchased was printed by Kessinger Publishing as part of their Legacy Reprints series. I’m thrilled to finally own the book. Many such POW memoirs have long been out of print and are hard to find.

The original subtitle for Keith’s book suggests the full sweep of his impressive adventure: An Account of the Service of a Christian Medical Corpsman in the United States Army Paratroopers during World War II, with Thrilling Stories of Training, Battles, Imprisonment, Escapes, Guerrilla Warfare, Hunger, Torture, and Faithfulness to Man and God.

Regarding the last item in the subtitle, I should mention that Keith, as a Seventh-day Adventist, abstained from drinking or smoking, studied his Bible daily, prayed for guidance and strength, and lived his faith to the best of his ability.

Keith’s memoir was written as a faith testimony, as is made clear an introduction by church elder C. Lester Bond: “ … the hero of this narrative, is only one of approximately 12,000 Seventh-day Adventist youth of North America who gave loyal service to their country while at the same time maintaining their devotion to God and His cause. Their faithfulness under the stress and strain of war has been a great inspiration to their fellow youth and to the church as a whole.”

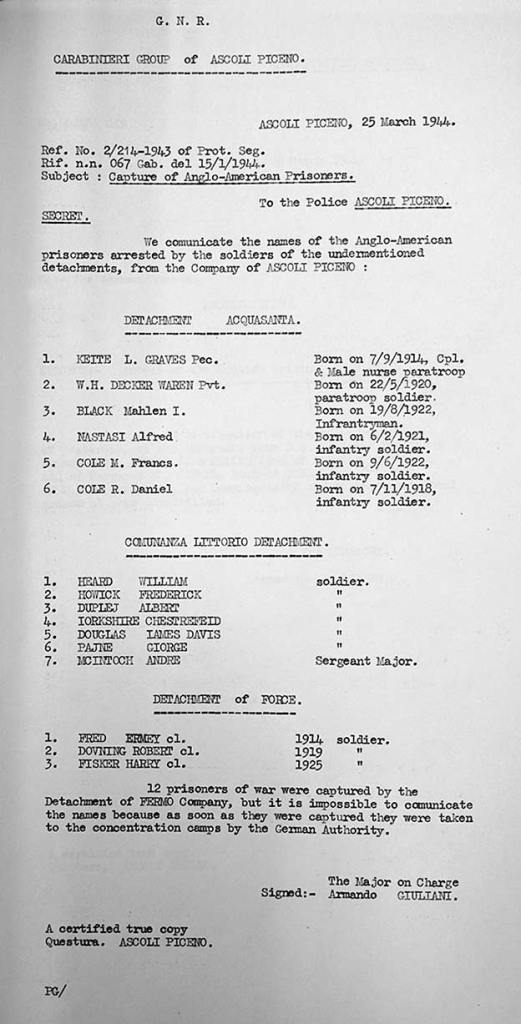

Keith acknowledged his fellow POWs in this dedication:

In APPRECIATION of the loyalty and fellowship of those who shared the dangers and sufferings of our lot as prisoners and fugitives, I dedicate this book to

Daniel and Francis Cole,

Warren Decker,

Mahlon Black, and

Alfred Natassi [Nastasi].

My friend Robert A. Newton, author of Soldiers of the Strange Night, profiled Keith in a chapter entitled “Brave Men.” I asked Robert if he had been in contact with Keith while researching his book.

Robert replied, “Keith had passed before I started my search, but I did speak to Warren Decker, also a paratrooper, on the phone. He told me about Keith’s book and sent me a photocopy. I also spoke to Alfred Nastasi. Several of the other ex-POWs I contacted asked about Argraves. He was widely respected and made quite an impression on his fellow internees. Some remembered him as ‘Hargraves.’ The fact that he escaped the clutches of the Germans several times is amazing.”

Keith knew from the start that he wanted to be a medic, and he specifically wanted to be a medic in the paratroopers rather than in an army hospital.

In joining the army, he was first assigned to the Fourth Division, 22nd Infantry, at Fort Benning, Georgia, a base where the paratroopers were in training.

At Fort Benning, Keith had the chance to apply for admission to the paratroopers. In his application he disclosed his firm religious convictions, stating the importance his being able to observe the Sabbath on the seventh day of the week, a day on which he would need to be released from duty. He also stated his refusal to carry a weapon.

In this, Keith Argraves was like J. Keith Killby, the founder of Monte San Martino Trust.

Keith Killby explained, in his memoir In Combat, Unarmed, how he pondered what role he could assume in defending his country and his loved ones: “My thoughts went round and round. I knew then that I could not kill a man who was innocent of all crimes against me or others, but was merely carrying out what he had been taught was right – just as I would be doing if I were to fight … I acknowledged that while I could not bring myself to fight, pacifism was not enough.” He needed to find his own way to stand shoulder to shoulder with his comrades in resistance to tyranny. Although he was to serve in the British armed forces, he was steadfast in his refusal carry a firearm.

Keith Killby’s pacifism was inspired by his conscience; Keith Argraves’ position was founded in his deep religious conviction.

The two soldiers were similar in other ways: Keith Killby requested assignment to the Medical Corps and ended up in the SAS, an elite British flighting group whose risky assignments were behind enemy lines; Keith Argraves joined the U.S. Army as a medic and requested assignment to the paratroopers, who stout-heartedly faced the toughest front-line missions.

Keith Argraves was admitted to the paratroopers. From Fort Benning, his battalion was transferred to Fort Bragg, North Carolina. Training continued, including day marches, night marches, and jumps. In time, Keith was sent overseas on the Queen Elizabeth. The voyage lasted five days, and the ship docked in Greenock, Scotland. The troops boarded trains for a camp near Hungerford, England.

At the Hungerford camp, the paratroopers were surprised by a visit from First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt. The commanding officer introduced Mrs. Roosevelt to Keith:

‘I want you to meet one of the bravest men in the battalion. He does not carry a gun when he goes into action. He is a queer sort of fellow because he has a funny religion. You can talk with him and find out about it.’

‘What is your religion?’ she asked Keith.

m‘I am a Seventh-day Adventist, adam,’ he replied courteously.

‘Where is your home?’ She questioned.

‘In Portland, Oregon, madam,’ responded the paratrooper.

‘Do you like the paratroopers?’ she inquired further.

‘I am not sure, madam,’ answered Keith.

‘How long have you been in the paratroopers?’ She continued.

‘A year, madam,’ was his reply.

‘You should know by now,’ suggested Mrs. Roosevelt.

‘This is a different game than I have ever been in before, and I am still undecided, madam,’ he averred.

‘It is different from what most people ever do,’ she agreed.

Changing the subject, she asked, ‘Is your clothing warm enough?’

‘No, madam, it isn’t,’ he stated. ‘The combat suits are too light for England.’

The entire group had reason to be grateful for her visit, for in a few days they received heavy socks and sweaters.

Keith’s battalion was moved to Land’s End, England, where final preparations were made for deployment.

Five hundred and twenty paratroopers were loaded into 37 waiting planes. As the grand armada of fighting ships prepared for the invasion of North Africa, the paratroopers took flight for Tafraoui Airport near Oran. Once captured, this airport would serve as the primary base for Allied aerial operations.

After Tafraoui Airport was taken, the paratroopers were transferred to the newly claimed Maison Blanche Airport near Algiers.

After about five days at Maison Blanche, the paratroopers left for a new objective. With them at this time was a battalion of British paratroopers. These and the Americans were to attack separate enemy objectives. One battalion was to go to Tunis, the other to Tebessa. To decide the issue, the respective commanders flipped coins. The toss decreed that the British were to go to Tunis; the Americans, to Tebessa.

The British went to Tunis and dropped on an airport there. But reinforcements never reached them, and they were encircled by the Germans and wiped out. Their destiny was determined by the flip of a coin!

Keith’s commander, Captain Carlos C. Alden, then assembled a team for a special mission, an assignment that the captain described as one “of such great danger that those who go will probably not return.” Medics would be needed, and Keith volunteered to go, saying “If the Lord wants me back, He will bring me back.”

Thirty-one personnel were assigned to the mission.

According to a website dedicated to the 509th Parachute Infantry “Geronimo” Regiment, this assignment was called the El Djem Bridge Mission—the main objective of which was destruction of the El Djem Bridge. The mission took place on December 26.

According to Keith, the broader purpose of the mission was to cut off Rommel’s retreat, so that he could then be entrapped by General Montgomery. Much was accomplished before the paratroopers were encountered by Germans. A few men escaped, but many were captured.

Keith was captured with Private Alkcus Stokes. The Germans confiscated Keith’s medical kit, watch, $150 in American money, and 9000 francs. The captives were marched about two miles to a waiting truck, where Keith and Alkcus were reunited with 17 of the American “suicide” mission group.

I’ve been able to confirm that at least seven of the men who were captured with Keith ultimately ended up in PG 59:

S/Sgt. Manuel Serrano, NCOIC (non-commissioned officer in charge)

Pfc. Leonard S. Caruso

Pvt. Warren H. Decker

Pfc. Hartwell R. Harris

Pvt. Clarence A. Howard

Pvt. James L. Rogers

Pvt. Alkcus Stokes

(Note—All seven of these men were first sent to PG 98 Sicily, arriving on 1 January 1943. They were later transferred to PG 59: Hartwell Harris and Clarence Howard arrived in PG 59 on January 13, James Rogers and Alkcus Stokes arrived January 21, Manuel Serrano and Warren Decker arrived January 23. and Leonard Caruso arrived February 5. These dates are from the prisoners’ Italian POW cards in the U.S. National Archives.)

The POWs were first taken to the harbor city of Sousse, where they were put under guard in a big garage on the docks. While interned in this garage, they were bombed by the US Army Air Corps.

Next they were transferred to the Tunisian Airport, where they were housed in a schoolhouse and forced to move German guns and ammunition. After seven days the captives were put aboard three Italian destroyers and locked below deck. En route to Sicily, the three ships came under Allied attack. Keith later learned that two of the three destroyers had been sunk. That was the last he heard of the prisoners on those ships.

On reaching Palermo, the prisoners were transported to PG 98, which Keith described in this way:

The men were placed in tents about twenty-five by sixty feet in size. Eighty-four captives were crowded into each of those miserable shelters. The bunks were made of slats and placed in double-tiered rows. The ground in the tents was a sea of mud under six to eight inches of water. One blanket, forty-two by fifty-four inches, was given to each man. These coverings were thin and too small to cover any but the smallest of the men.

Rain, sleet, or snow fell almost constantly. Driven by the freezing January wind, the damp cold seemed to penetrate to the very bones of the wet, hunger-weakened prisoners.

In their endeavors to shut out the ever encroaching cold, the men tied the tent flaps when they retired for the night. But the Italian guard checked them five or six times during the nocturnal watch. Instead of untying the strings that held the tent flaps, the guard cut them, thus leaving the tent wide open to the wintry blasts. To add to the misery of the prisoners, he hit each one of them on the head every time he passed by. The prisoners were forced to sleep with their heads to the aisle to make this practice possible.

Hardly enough food was furnished to keep the dimming flame of life burning. For each twenty-four hour period the men were given one half of a pint of soup made of macaroni, rice, and beet tops, and four ounces of white bread. The grass in the courtyard was pulled and eaten by the prisoners. The ground outside the fence became bare as far as they could reach. Slowly but surely they were dying of starvation. Every day men died, with starvation as the principal cause.

After 40 days in PG 98, Keith and around 500 Americans were loaded onto a train for transport to Messina. It was March 1943.

In being transferred from PG 98 to being moved to PG 59, Leonard Caruso, an Italian-American soldier, was diverted to PG 50 on January 13 for interrogation. Keith mentions of this diversion of Italian-American prisoners from the train in Naples to PG 50 Rome:

Fifty Americans of Italian descent were taken from the prison train [in Naples] and sent to Rome.

‘Why are you fighting against Italy, your native country?’ They were asked.

‘We are citizens of the United States!’ they replied. ‘The United States has been good to us! Our homes are there, our friends—’

‘Traitors!’ cried the angry officials. ‘Let them be punished.’

These prisoners were beaten and otherwise mistreated before being sent on to the prison camp [in Servigliano].

They were unloaded in Messina, ferried to Reggio di Calabria, and then crammed again “at the point of a bayonet” into small Italian box cars—forty-five to sixty men to a car. The transport took four days and three nights. Very little food was given to the prisoners, and no water was provided for the first three days of the trip. When the men arrived at PG 59 Servigliano they were examined and treated by the senior medical officer of the camp, Captain J. H. Derek Millar. Keith explains that Dr. Millar did a good job of caring for the men, despite the fact he had very little equipment: “With a little medicine that he had procured from an Italian doctor, and some that arrived in Red Cross parcels, he almost worked miracles for the men in camp. He even performed operations with a razor blade!”

Conditions at this camp were better, although rules were rigid. Red Cross food parcels were distributed each week, and this supplemental food was essential.

The memoir describes general conditions in the camp, the camp scourge of bedbugs, the digging of escape tunnels, and Keith’s experience in solitary confinement. Finally, he describes the breakout from PG 59 in September 1943.

According to a plan made before the escape, Keith and seven of his friends had selected a meeting place in the mountains. In the camp they had studied maps of the area. One escapee had a compass. After the breakout, at the agreed-upon meeting spot, all seven were reunited.

The men traveled by night, avoiding trails and roads. During the day they hid in ditches and concealed themselves with brush. They had with them some food from Red Cross parcels, and they filled several wine bottles with spring water. At night they plundered tomatoes, carrots, and beets from a garden, and raided a vineyard for “a royal feed on grapes.”

But most of all, mused Keith, the fellows longed for home-cooked meals they had enjoyed in the States:

‘Boy, wouldn’t a thick steak taste good?’ asked [Warren] Decker. ‘I want a steak big enough to shake hands with!’

‘That’s nothing!’ retorted [Mahlon] Black. ‘How about one big enough to milk?’

‘M-m-m! Smothered in onions—and with baked beans and mashed potatoes!’ said one.

‘Topped off with pumpkin pie!’ added another.

‘I’ll take apple pie for mine!’ suggested still another.

‘Any old kind of pie will do! Just put some ice cream on top!’ was one suggestion.

‘Stop, follows, stop! You’re making my stomach hurt!’ commented one of the men.

Al Nastasi, one of two in their group who could speak Italian, was the first to approach a local. Seeing a fresh string of fish hanging from the porch of a house, he began a conversation with the farmer who lived there. The farmer offered his fish to Al, but Al declined—instead, returning to the group with a hook and line in his pocket! The men caught enough fish in a local creek to appease their hunger for the evening. They cooked their meal over a cedar wood fire.

Traveling further south, the men approached a village at daybreak.

The people were very friendly, inviting them to sleep on the hay in a barn, and assuring them that they would feed them. Gratefully the weary men accepted the kind invitation and slept through the day. The Italians kept their word, seating the men around the table on which were five enormous platters of spaghetti. This and two fried eggs for each man disappeared completely as they ate their first good meal they had had since they were taken prisoners by the enemy months before.

Their friendly hosts invited them to stay with them. ‘There are no Fascists in the village, and no one will turn you in,’ they urged.

In a home in the area where there was a radio, the two Italian-speaking escapees heard welcome news of Allied progress.

However, an Italian station broadcast a warning to locals to look out for escaped POWs and announced that 3,600 lire was being offered for each man, dead or alive. “Chills chased each other up and down the spines of the two men while they thought of themselves as fugitives with a price on their heads!” Keith recalled.

They left that village and continued south. Two of the men pressed on, and Keith later learned that they reached the Allied lines and were sent home. The remaining men were fired on several times and narrowly escaped injury. One of the Cole brothers fell from a 15-foot embankment during flight and severely sprained an ankle; the other brother seriously injured a foot.

Around the Pescara River they found a heavier German presence and they felt that to continue the southward journey was too perilous. In order to avoid detection, they climbed higher into the mountains. They found a warm welcome in the village of Falciano. An Italian army captain, Saturnino Brandimarte, who had disbanded his men after Italy’s capitulation, sought refuge in Falciano. Captain Brandimarte spearheaded the effort to protect the Americans. Several Falciano households contributed in various ways.

At one point the men heard of plans for a boat rescue along the Adriatic and made their way to the coast. Nearing the coast, they joined other escaped prisoners. They had missed the first boat; they waited three days for another call. That night boats appeared off the coast and the men waited in the darkness, uncertain of whether they were skippered by friend or foe—until a searchlight swept the beach and they were fired upon. Some were injured or killed. Keith’s group narrowly escaped and returned to Falciano.

In time, assisted by paratroopers, the group made one more attempt at sea escape. Again, they encountered the enemy, were fired upon, and retreated to the mountains.

They learned of a guerrilla band operating in the area. Since escape at proven futile, they decided to join this band and fight against the Germans and facists.

The band was led by a Russian major and a New Zealand major who were both escaped prisoners of war. It was comprised of around 400 soldiers from various countries. Gasoline and ammunition dumps were attack targets, and the group destroyed bridges and communication lines. “Like tiny dogs biting at the heels of an enraged bull,” the memoir states, “these guerrilla bands distracted the enemy, and forced him to patrol the areas to his rear.” Eventually the American Army Air Corps dropped supplies for them. The fascists seized much of these supplies, but the band was fortunate to claim a portion, which included food, clothing, and two-way radio sets.

Many of the Italians were friendly and helpful to them. However, for the guerrillas this activity felt like a losing battle.

The end of the year brought cold, clammy weather and little snow, but at the end of December winter at last took a firm grasp on the Apennines.

When January 1, 1944, dawned, it came upon a world of white. Fences had disappeared, travel had ceased, and the cottages on the mountain looked like great mounds of snow. In thirty-six hours five feet of snow had fallen. In the first two days of the new year, another foot of winter’s thickest blanket in sixty years covered the mountains.

The men helped shovel snow from their Falciano protectors’ roofs and cleared paths to outbuildings. The villagers invited them to stay in their houses at night, but the men refused the offer, as they could more easily be captured in homes.

In the village lived a German priest who claimed he had left Germany because of religious persecution. It turned out he was a German spy, who sent word to the fascists that Allied prisoners were hiding in Falciano. One evening, as Keith and his five friends were enjoying the warmth of an Italian home, the doors burst open and they were accosted by German ski troops in white uniforms. The men had no chance of escape. According to Keith, every house in the village was searched that night, and 80 escaped prisoners and some Italians were rounded up. The prisoners were asked to produce identification; those who lacked identification were lined up and shot before the eyes of their horrified comrades.

After four and a half months at liberty, Keith and his friends were headed once again for imprisonment. The six friends were first jailed for three days at the fascist headquarters in Aquasanta. They were then marched through Ascoli, where they were held for an additional 20 days. On the final two days of their stay, the captives were confined to a large room on the building’s top floor with about one hundred other Americans, New Zealanders, Australians, Canadians, Yugoslavs, and Russians.

The six were moved to Camp 53, which was a Jewish internment camp, for a few days; then they were transferred to Camp 132 near Rome.

They were told they would be marched to the next internment camp. Two thousand prisoners—mostly Yugoslavs and Poles—were marched 70 miles to Camp 82. It was a gruesome march, Keith explains, overseen by a body of “Hitler youth.”

“With itching trigger fingers, the young Germans shot every prisoner who stopped without being ordered to do so. They even shot those who fainted.” After 50 hours of almost steady marching, only about 500 of the original 2,000 reached the destination.

Keith was held in Camp 82 for about 80 days. At last, the prisoners were herded onto a waiting train for transport to Germany. Prison trains were supposed to have been marked “POW” so that the Allies would not regard them as military targets, but the Germans had not marked this train.

All went well until the train neared Florence. It was crossing the Arno River when train was bombed by the U.S. Army Air Corps. When Keith’s box car was blown open, he and the others ran out. They were stopped by the Germans and forced to lie flat. The guards had not stopped to unlock the other cars, and a horrific scene unfolded. “The remaining cars were on fire by this time,” Keith relates, “and the screams of the trapped men were heart rending. After what seemed ages the attack was over, and the fire had completed the horrible work begun by the bombs.”

The survivors buried the dead, a mournful two day task. Afterward they were marched to a temporary prison camp where they were held for a few days.

Reboarded on a new train, the prisoners headed for the Brenner Pass. Keith had managed to conceal a Boy Scout pocketknife, which now he and several other prisoners used to cut a hole in the back of their boxcar. Three men, including Keith, exited the car and dropped onto the tracks. They split up and Keith headed south, avoiding larger villages and approaching Italians for food. After only three days on the run, he was captured by fascists and again found himself aboard a northbound train.

Incredibly, Keith soon found another opportunity for escape.

During a stop, a guard had come by with a five-gallon can of drinking water. The guard opened the door of the box car, set down the can, and went on to the next car. Quick-thinking Keith and a prisoner named Cliff slipped out and stretched out on the track beneath the car. Soon the train started moving; as it pulled out of sight into darkness, the two men rose to their feet. This time they were in Germany. Their freedom was short-lived, as they were soon recaptured.

On arrival in Stalag 7-A, Keith was reunited with Dan and Tony Cole. Keith was so emaciated that the brothers at first didn’t recognize him. The two helped to care for Keith, gave him the milk from their Red Cross parcels, and advocated for his medical care. Dan Cole was transferred to Stalag 2-B; later his brother was reunited with him there.

In time Keith grew stronger. Twenty-five days after Keith was released from the prison hospital, he was transferred to Stalag 2-B. He immediately searched along the prisoners for the Coles, only to learn they had been transferred to Stalag 3-B several days earlier.

However, in Stalag 2-B he was united with Warren Decker and Mahlon Black, whom he had not seen since leaving Italian Camp 82. Keith describes at length the inhumane treatment and executions of prisoners in this camp, especially the Jews and Russians, who were “special objects of German wrath and mistreatment.”

In time, Keith was transferred again, this time to Stalag B-3 and reunion with the Coles. Harsh treatment of prisoners was the rule in this camp also. In time they were heartened by the spectacle of great fleets of Allied planes overhead, and they could hear the bombing of Berlin some 35 miles away.

One day, unexpectedly, Keith found himself homeward bound. The Germans read aloud a list of prisoners who would be released. Seventy-four medics were named. According to the Germans, their release would be that very afternoon; in preparation these fortunate men was issued new uniforms.

It turned out the medics were being exchanged for 71 German nurses.

Fourteen days of transit, with stops and transfers along the way, took them through scarred landscape and shattered German cities. Finally they found themselves aboard a train bound for the Swiss border.

The group rested briefly in Geneva before moving to Marseille, France; in Marseille they were rested for about six weeks. They then boarded the hospital ship Ernest Hinds, which was bound for the States.

After 17 days of pleasant sailing, America came into view. As they landed in Charleston, South Carolina, two bands played to welcome the returning soldiers. Among the tunes played, Keith particularly remembered “Don’t Fence Me In”!

Keith soon found himself aboard a train bound for Portland, Oregon. He celebrated his homecoming furlough with family and his friends, eventually returning to work, but only for a few weeks, as he neared his discharge and return to civilian life. As time passed, Keith learned that all five men with whom he had shared his epic adventure had returned home safely. He also heard from Captain Saturnino Brandimarte after his return to the States.

In years to come, Keith would tell the story of his wartime experience over the radio, in lecture halls, and to church groups. He never forgot the kind Italians who risked their lives to protect him.

Keith L Argraves / TEC 5 US Army / Sep 7, 1914 – Nov 24, 1974

For more information, read the biography of Keith Lamar Argraves on the website of the Encyclopedia of Seventh-day Adventists.